« July 2011 | Main | September 2011 »

August 30, 2011

Road to Nowhere

Monte Hellman - 2010

Monterey Home Video Region 1 DVD

In an early scene where the director, Mitchell Haven, and the screenwriter, Steven Gates, meet with a producer, Gates blurts out, "This is the film noir of our dreams". But what Gates is referring to is not the realization of a film that meets, or exceeds, the expectations of genre. Instead, Road to Nowhere, both the film we watch, and the film (or is that films) within the film, can be thought of as dreams as film noir. More specifically, as in a dream, there is a continuity of events that take place, in this case a mystery, or series of mysteries. And as dreams, at least the ones I vaguely remember, go, they don't always make a lot of sense when awake, but I feel like it is a mistake to insist that a dream does make sense.

One of Monte Hellman's dream projects was to make a film version of Alain Robbe-Grillet's La Maison de Rendez-vous. Robbe-Grillet's work in literature and film is often concerned with differing points of view, and memories that may possibly be contradictory. What is of interest here is not a narrative that cleanly progresses from one point to another, but something that shifts around almost at will. What one looks for is not a story in the traditional sense but in literary terms, the pleasure of the text, to borrow a phrase from Roland Bathes, or in film, the pleasure of the succession of images.

The bulk of Road to Nowhere a film within the film, with a DVD of that title inserted in a player. There are also scenes of Mitchell Haven and his muse, Laurel Graham, watching movies on television, with excerpts from The Lady Eve, Spirit of the Beehive and The Seventh Seal. The excerpts are chosen as commentary on what is to come. Additionally, there are lots of shots involving mirrors and windows, reflecting light and shadows. Rather than making simply a movie about the making of a movie, many of the shots visually refer to those words used to describe movies.

While watching Spirit of the Beehive, Laurel tells Mitchell, "You disappear into your dreams". In a sense, that's what watching a movie is all about. Possibly someone smarter than me could really tell you what Road to Nowhere is really about. Me, I dropped off the film theory train during the time that semiotics was in vogue. Not only could I not recount the multiple stories within Road to Nowhere, I'm not sure if I really care for an explanation, were one available, nor do I think it really matters.

What matters more to me is that first image of Shannyn Sossamon holding one of those hair dryers that looks like a gun, pointing at herself, Dominque Swain in her white underwear, the movement of the shadows on the illuminated fountain while Sossamon and Tygh Runyan sit in the dark, the shocking image of the small airplane diving into the water. Too many films seems to rely on over-explanation. Road to Nowhere is dialogue free for about the first ten minutes, and one of the first sounds heard is a scream in the dark. Imago ipsa loquitur - the image speaks for itself.

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 08:43 AM | Comments (2)

August 28, 2011

Coffee Break

Alexandra Hay and Gary Lockwood in Model Shop (Jacques Demy - 1969)

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 08:43 AM

August 25, 2011

Don't Torture a Duckling

Non si sevizia un paperino

Lucio Fulci - 1972

Shameless Entertainment Region 0 DVD

At the time I received my preview copy of Don't Torture a Duckling, the riots that burned down the Sony warehouse had not happened. This review is posted a few days in advance of the official release date. As Shameless was one of several DVD companies affected by the riots, the release date and availability of this DVD may be affected. Considered by some to be Lucio Fulci's best film, this is one which would benefit the most with some accompanying material to put the film in greater context, both as part of Fulci's filmography, as well as the concerns raised in the subject matter. I should note that the DVD comes with notes by Stephen Thrower from his study of Fulci, Beyond Terror, but I have read neither those notes nor the book. Compared to some of Fulci's other films, the narrative aspects were done with greater care. Even so, what I suspect is that Fulci used some of the trappings of the mystery primarily to address other concerns.

The film takes place in a small, out of the way, Italian town called Accendura. Several young boys are found murdered, all strangled. The police investigate several suspects. A big city newspaper reporter also worms his way into the investigation, sometimes helping the police. The town is like some shown in other Italian movies, where everyone seems to know everyone else, the local women all dress in black, and strangers are regarded with suspicion. The town is off of a major highway, providing simply symbolism for a place stuck in time while the future speeds by.

The three leading suspects are outsiders of different kinds. The first is a mentally handicapped man who jeopardizes himself until it is clear that he is unaware of the implications of his actions. The second suspect is a woman, Maciara, reputed to practice witchcraft. There is finally the young woman, Patrizia, from Milan, the daughter of a man from the small town who found is fortune in the big city. The young priest mentions to the reporter that strange incidences in town have coincided with Patrizia's arrival.

What Fulci seems to be primarily interested in here is attacking small town conformity, with a side swipe at some of the dogma of the Catholic Church. The townspeople are eager to find someone to accuse and punish for the murders. The insularity of the town in reinforced when the priest mentions that he does not allow certain newspapers and magazines to be made available. Maciara and Patrizia pose as the greatest threats because they are both single women in a town where women are almost invisible, and are both fiercely independent. Patrizia's very sexual presence stirs the imagination of some of the pre-adolescent boys who have been discovered dead.

One of Lucio Fulci's films still unavailable as a subtitled DVD is the one he has stated is his favorite, Beatrice Cenci. Not a horror film, but in part a critique of the Catholic Church in a late 16th Century setting. Having this film available might be key in discussing how religion is treated in Don't Torture a Duckling, as well as reminding even his most rabid fans that Fulci was more than the purveyor movies about eye gouging and zombies.

There are some actors of note here: Tomas Milian, Barbara Bouchet and Irene Pappas. (One could program a double feature of Barbara Bouchet movies that feature headless dolls, with The Red Queen Kills Seven Times.) The film belongs to Florinda Bolkan. Never more feral on screen than in the opening shots where we see her clawing at the dirt, uncovering a small skeleton. Fulci's close ups provide a geographical study of Bolkan's face when she bares her teeth and stares straight into the camera. Bolkan is also in the most brutal scene in Don't Torture a Duckling, albeit one that is not exploitive. It is no small coincidence that Bolkan starred in Fulci's other best animal titled film, Lizard in a Woman's Skin. Whatever one might think of Lucio Fulci and his films, he tapped into the certain strengths, a physicality, that Florinda Bolkan possessed, bringing it out in full force, literally seen in her ripped flesh.

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 08:00 AM

August 23, 2011

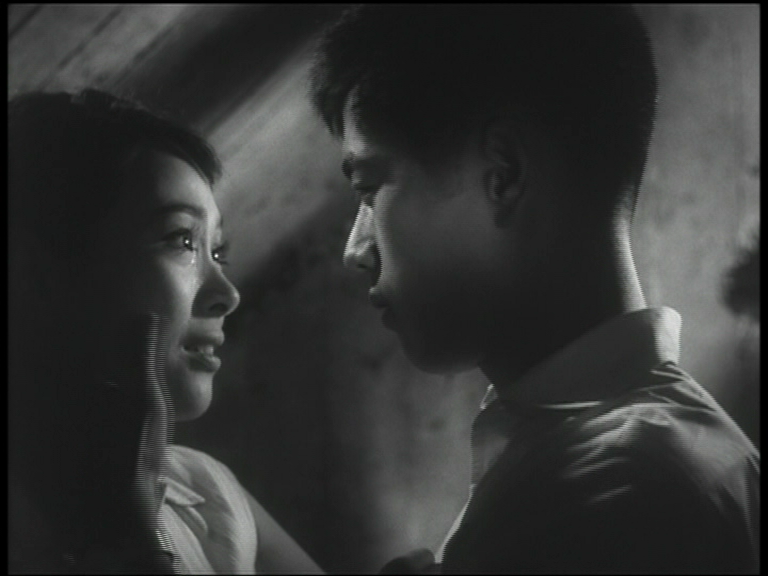

Kokoro

Kon Ichikawa - 1955

Eureka! Masters of Cinema Region 2

There's a shot in Kokoro of a foot literally stuck in the mud. It's a fitting visual metaphor for the character, Nobuchi, who finds himself unable to move from his own emotional trap. Many of the scenes in Kokoro also involve rooms, and opened or closed doors, emphasizing the characters' own closing off from each other.

Even when the film is a studio assignment, as Kokoro, there is still thematic continuity. The central question is about choices that are made, rightly or wrongly, that put the protagonist in a moral quagmire. One part of the story is a flashback, taking place in about 1897, about Nobuchi and his best friend, Kaji. The two young men, soon to graduate from university, have differing opinions about how to live. Nobuchi expresses skepticism regarding Kaji's choice to live an ascetic life following Buddhist principles. The two rent rooms, where they unavoidably develop interest in the landlady's daughter, Shizu.

The framing narrative is about a young student, Hioki, who first comes across Nobuchi by accident, perceiving the older man to be drowning in the ocean. For reasons never made clear, Hioki decides to make Nobuchi his mentor in life, even though the older man's life consists of nothing more than scholarly pursuits. Nobuchi is married to Shizu, in a relationship that is often punctuated with arguments and misunderstandings, based, as is eventually revealed on Nobuchi's relationship with Kaji.

There are aspects of the film that may be lost, even with some general understanding of Japanese history. The film was based on a novel by Natsume Soseki, taking in some of the general themes of the author. 1912 marked the end of the Meiji era and the beginning of the Taisho era in Japan. Even though the Meiji era marked the beginnings of "modernization" in Japan, and the end of the feudal era, the differences in generations can be seen with Nobuchi always in a kimono, while Hioki is periodically shown wearing western style clothing, the student uniform of the day. The changes in eras allows for a look at contrasting the connections of the historical past with the emotional past. Kokoro also provides an interesting comparison to The Burmese Harp not only for its fatalism, but also how in the latter film, the young soldier pretends to take on a Buddhist practice only to have it evolve into something both serious and ultimately liberating.

Michiyo Aratama as Shizu was twenty-five when she made Kokoro. With only a change in hairstyle, she is transformed from a younger woman who encounters Kaji and Nobuchi, to a woman who has been married to Nobuchi for thirteen years. I've seen Aratama in other films, but never was struck by her as I've been in this film. She doesn't have the kind of more obvious kind of beauty of Ayako Wakao, or someone like Machiko Kyo when she plays a modern character. Aratama has the kind of understated beauty that gradually grabs your attention, at least in this film. Kokoro is the Japanese word for heart, and Aratama is the true heart of the film around which everyone else revolves.

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 08:34 AM

August 21, 2011

Coffee Break

Aksel Hennie and Christian Rubeck in Max Manus (Joachim Rønning & Espen Sandberg - 2008)

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 08:14 AM

August 18, 2011

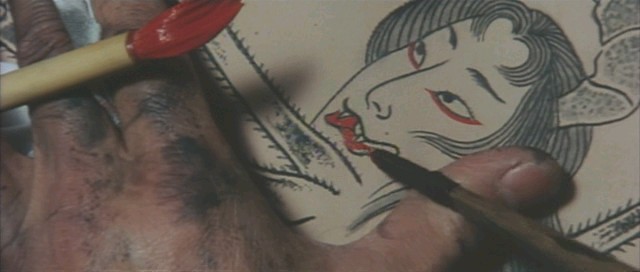

Irezumi

Yasuzo Masumura - 1966

Yume Pictures Region 2 DVD

Is there anything to explain why Kaneto Shindo, a director in his own right, served as screen writer for two films directed by Yasuzo Masumura, both based on the writings of Junichiro Tanizaki? The better known of these two films is Manji, also starring frequent Masumura muse, Ayako Wakao. Irezumi has recently been screened as part of some retrospectives, providing this film a higher profile.

Otsuya, the daughter of a pawn broker, runs away with her lover, Shinsuke, the apprentice to her father. I'm unsure about the time period as everyone wears kimonos, but I'm guessing near the end of the samurai era in the 19th Century. Taken in a family friend, Otsuya is kidnapped and sold to a geisha house, while Shinsuke is taken others to be killed. Shinsuke manages to kill his would be murderer and lives the life of a fugitive. Otsuya is further objectified when an artist is allowed to tattoo a giant spider on her back. The spider, with the face of a female demon, is the alleged cause of Otsuya taking advantage of various men in her life, leaving them at best without money, or at worst, without their lives.

In several ways, Irezumi is the opposite of Masumura's Kisses. Unlike the earlier film, where the characters take responsibility for their actions, the characters here blame outside forces for their transgressions. Rather than trying to live pure lives in an impure world, Otsuya and the others dive straight into the cesspool. Also, unlike the natural, and real life settings of Kisses, Irezumi was shot entirely in a studio, with unnatural appearing exteriors. In one scene, Otsuya and Shinsuke are standing on a bridge in the snow. Otsuya threatens to drown herself in the water below the bridge which remains unseen. Masumura barely disguises that the scene could just as well have been taking place on a theater stage. And as Kisses ends optimistically, Irezumi ends with the death of virtually every major character.

Masumura is said to have been unhappy with the cinematography by Kazuo Miyagawa, although that didn't seem to stop them from working in the future. What is most visually interesting is how some of the scene are framed. Almost like the layers of Ayako Wakao's kimonos, not everything is revealed with the scope screen. Parts of the frame are blocked off with shoji screens, walls, doors, or simply the positioning of the actors. The emphasis would be on the insularity of the characters, most of whom find themselves emotionally, if not physically trapped.

Ayako Saito has an essay on the collaboration between Masumura and Wakao. What makes Irezumi of interest is that it is both self-critical and self-contradictory. In Masumura's films, Wakao plays women who can be described as independent and self-assertive, unlike the traditional portrait of Japanese women. Otsuya is essentially made into an object for the benefit of the male gaze, yet turns her status as a way of extracting revenge on those who would use her for their own sexual or financial benefit. To some extent, the primarily male audience, for whom the film was made, as well as the filmmakers, are implicated with the frequent shots of a partially nude Wakao, where she displays her back and the tattoo. The essay, found in the collection, Reclaiming the Archive: Feminism and Film History explores not only what is to be seen in the films made by Masumura with Wakao, but also the extent to which Wakao expressed herself artistically rather than simply serve the director's muse.

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 08:00 AM

August 16, 2011

Kisses

Kuchizuke

Yasuzo Masumura - 1957

Yume Pictures Region 2 DVD

Sweet is not the first word grabbed to describe a film by Yasuzo Masumura. Not as well known to western audiences as some of his peers, Masumura's reputation mostly rests on a handful of films that have received subtitled DVD releases. Blind Beast, from a story by Edogawa Rampo, emphasizes the twining of the erotic and the grotesque obsession of a blind sculptor and a young woman, while in Red Angel, Ayako Wakao finds danger everywhere in the World War II drama. Kisses may seem like an extraordinary film in the context of Masumura's career if only because the two main characters are relatively ordinary.

In his book that primarily covers Japanese filmmakers that emerged in the Sixties, Eros plus Massacre, David Desser quotes Nagisa Oshima: "In July, 1957, Yasuzo Masumura's Kisses used a freely camera to film the young lovers riding around in a motorcycle. I felt now that the tide of a new age could no longer be ignored by anyone, and that a powerful irresistible force had arrived in Japanese cinema."

Jonathan Rosenbaum provides a deeper look at Masumura's career. The neo-realistic influences are clear throughout Kisses, and a reminder that it was Italian neo-realism that provided one of the main influences for the French Nouvelle Vague. Rosenbaum's article is of interest in pointing out some of the similarities between several of Masumura's films and those of Hollywood filmmakers that the Cahiers du Cinema gang had championed. As Rosenbaum points out, Kisses was neither a commercial nor critical success at the time of release. I have to assume that the reason the film was produced, and assigned to Masumura as his debut was in response to the youth oriented films that Nikkatsu Studios released at about the same time.

The film covers a two day period where Akiko and Kinichi meet, separate, and finally come together again. Their respective fathers are both imprisoned, Akiko's for embezzling money to pay for his wife's medical treatment, Kinichi's for some never clearly explained election fraud. Kinichi sees Akiko berated by a prison clerk for not paying for her father's meals, and impulsively hands over enough money to cover the fees. Akiko chases Kinichi down to thank him. A bet at a bicycle race determines whether the two will spend the rest of the day together. Akiko wins the bet, and the pair spend the day at the beach, roller skating, eating, drinking and dancing. In addition to having their fathers in prison, Kinichi and Akiko are concerned with ways to come up with the 100,000 yen needed for their parent's release.

While the initial setup is contrived, what makes Kisses different from the Nikkatsu films is that the characters live in a mundane world. Kinichi, a university student, gets by working as a delivery driver for a bakery. Akiko works as a nude model for painters. The two live modestly in shabby quarters, when money, or more often the lack of money, dictates their lives. Unlike many youth oriented films where the parents either do not exist or are marginal, part of the narrative here is of children who seek to redeem their parents, in the moneyed sense of the word, and simultaneously prove their own worth, again in a literal sense.

The actors who played Akiko and Kinichi, Hitomi Nozoe and Hiroshi Kawaguchi, might well have been cast because they were the same age as their characters, 20 and 21. Both appeared in other Masumura films, together also notably in Giants and Toys, as well as Yasujiro Ozu's Floating Weeds. Both began their careers shortly before Kisses, and both cruelly died at relatively young, Kawaguchi at 50, and Nozoe at 58. There is very little about either actor in English, although Nozoe's most notable appearance would be as the victimized model in Blind Beast.

Where Kisses is different from other Masumura films, and other films centered on young people is the sense of reconciliation that concludes the story. While Masumura's aim was to remove the sentimental aspects from the source novel, the ending, even if it may be considered conventional, is still satisfying, perhaps because it suggests a hopeful future.

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 07:42 AM

August 14, 2011

Coffee Break

Julia Roberts in Duplicity (Tony Gilroy - 2009)

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 08:58 AM

August 11, 2011

Almost Human

Milano odia: la polizia non puo sparare

Umberto Lenzi - 1974

Shameless Entertainment Region 0 DVD

Shame on me. I had no idea over five years ago that s second DVD version of a film I wrote about would come my way. Back when this blog was barely a crawling infant, a still new DVD label called NoShame had me on their screeners list. Almost Human was one of the first films I wrote about, along with another police thriller. I no longer have that DVD to compare with the new version from Shameless, but again, since NoShame has sadly gone belly up, this film is again available. Shameless even has included the Thomas Milian interview that was included in the NoShame DVD.

Umberto Lenzi grabs your attention with three bank robbers donning grotesque masks prior to a robbery. The wheel man, edgy and impatient, loses his cool when a street cop approaches about a possible parking violation. The cop is shot point blank, and the wheel man and the bank robbers embark on a high speed chase through Milan. Eluding the cops, it turns out that that the guy behind the steering wheel is a small time hood who gets beaten by the mob for his incompetence in blowing the bank job. The driver, Giulio Sacchi, has a big mouth, big dreams, and a plan to make a big score.

Almost Human is described by some writers as being part of the poliziotteschi genre, Italian films about policemen largely inspired by Don Siegel's Dirty Harry. That classification doesn't quite fit here as the main character is the small time hood, Sacchi. The character, as played by Thomas Milian, fueled largely by drugs and alcohol, made me think of an even more manic and dangerous version of the character Johnny Boy, played by Robert De Niro in Mean Streets. Did Lenzi or screenwriter Ernesto Gastaldi see that film, perhaps at Cannes in 1974? Another possible influence might be the classic High Sierra, with Humphrey Bogart as "Mad Dog" Earle. Certainly, Lenzi has stated his admiration for Raoul Walsh, One can see both some similarities in story elements, a robbery gone wrong, and a car chase, but mostly Sacchi is like Earle in cruelty towards his own gang members, but without Earle's humanity that almost redeems him.

Sacchi and his two lunkhead companions kidnap the daughter of a wealthy businessman. Along the way, others are killed, including Giulio's too trusting girlfriend. In pursuit is Walter Grandi, a no nonsense detective who puts the pieces together. As played by Henry Silva, in one of his rare good guy roles, Grandi is a cop you should be afraid of. Ultimately, it is Sacchi, in his megalomania, who undoes himself. This is a very unadorned film with no time for lyricism. Ennio Morricone's propulsive music is much the same way (turn up the bass), charging forward. And if you still need another reason to add this film to your collection, the first 1000 copies of the Shameless DVD have this special lenticular cover art.

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 08:51 AM

August 10, 2011

Fire Sale

For those who haven't read the news, the London riots have affected cinephiles. I have no clue regarding the motivations of those who torched the Sony warehouse, but I can tell you that I'm personally affected by what has happened.

It's the smaller DVD labels that allow us to still see, and appreciate, various films, classic or not-so classic, that might otherwise be unavailable. And the people who run these labels are mostly just getting by, just like the rest of us. I received an email from Valentina Sutto of Shameless indicating her optimism following the loss of stock. There's more about the DVD labels that have been hit in this post from V Cinema.

Insurance doesn't quite cover everything. So if you ever wanted a reason to do a little shopping at Amazon.UK (not an affiliate of this site, by the way), here's a good excuse to help out the people who share their real love of cinema with the rest of us.

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 01:15 PM

August 09, 2011

The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh

Lo strano vizio della Signora Wardh

Sergio Martino - 1971

Shameless Entertainment Region 0 DVD

Two words: Edwige Fenech. This is the film that made the young actress a star primarily in Italian film throughout the Seventies. And yes, there are some nude shots, but best of all are the close ups of that still photogenic face. In the meantime, after a bit of a lull, the British company, Shameless, is back on track with new DVD releases. Especially as the previous DVD release, from NoShame, is out of print, a new DVD release of The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh is very much welcomed.

Taking place in Vienna, the film begins with a quote from the Viennese Sigmund Freud, and plays with some psychological concepts. The wife of a diplomat, Julie Wardh is pursued by an past lover, Jean, with whom she have a relationship based on rough sex. Married or not, Jean still sends a bouquet of roses, refusing even the most clear refusals. Julie's marriage is loveless, and she succumbs to the advances of George, a stranger from Australia. In the meantime, there's a mad killer on the loose murdering attractive young women with a straight edged razor. As this is giallo, everything does come more or less together, although in ways not entirely expected.

While I loved the NoShame DVDs for their interviews with the cheerfully ingratiating screenwriter, Ernesto Gastaldi, the extras here are worth mentioning. The Shameless series frequently uses a "Fact Track", subtitles that discuss aspects of the film being watched. The commentary by Justin Harries is more serious and informative than some of the commentaries of other releases. In this case, not only does Harries discuss aspects regarding the making of the film, but also connects Mrs. Wardh not only to the obvious proto-giallo, Les Diaboliques, but also, unexpectedly, The Wind, Victor Sjostrom's 1928 film with Lillian Gish going crazy over both real and imagined fears. There is also an interview with Sergio Martino discussing Mrs. Wardh and his career in general.

A credit that caught my eye was that the music was scored by Nora Orlandi. And it is a catchy score, recycled by Quentin Tarantino for Kill Bill, Vol. 2. I mention this as there are so few women even now who compose film scores, and those of previous era, like Orlandi and Elisabeth Lutyens, are barely remembered today.

Sergio Martino might not be the visual stylist on the level of Dario Argento or Mario Bava, but there are several close ups using light and shadow that make the most of the face of Edwige Fenech. And while Martino freely admits that much of the nudity in the film, with Fenech and some other actresses, was commercially motivated, I'm not one to argue that any of it was gratuitous. There is the killer, or is it killers, with the black gloves. For those merely interested in a film that fulfills genre requirements, Mrs. Wardh succeeds on that level. What other films don't have is that one delirious, extreme, and upside down close up of the large, faintly exotic brown eyes and very long eye lashes of Edwige Fenech.

************

I have received an email from Valentina of Shameless informing me that the label has also been affected by the Sony warehouse fire that has destroyed the available stock of several smaller DVD labels. If you have an excuse to treat yourself to some films, check out the link above. Thank you.

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 07:41 AM

August 07, 2011

Coffee Break

Setsuko Hara in Early Summer (Yasujiro Ozu - 1951)

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 08:46 AM

August 05, 2011

The Woman in the Rumour

Uwasu no Onna

Kenji Mizoguchi - 1954

Eureka! Masters of Cinema Region 2 DVD

Released about five months prior to Chikamatsu Monogatari, The Woman in the Rumour (and yes, I'm using the British title here), was a studio imposed project. The story is essentially about a young woman, Yukiko, who returns home following a suicide attempt, after a broken engagement. Her fiance's family objected to Yukiko's mother running a Kyoto brothel, still legal during this time. The mother, Hatsuko, brings in a doctor, Matoba, to examine Yukiko. While the daughter gradually opens up about her disappointment in love, and her objections to the brothel, Hatsuko looks to setting up the young doctor with his own practice, and a more intimate relationship. Things go badly when Matoba reveals his love for Yukiko. The younger women, meanwhile, sees how her mother supports her employees, who often work out of economic necessity on behalf of their respective families. The title refers to Hatsuko, who is unaware of how others see her relationship with Matoba.

I might sound heretical to some, but when I saw this film I thought about Douglas Sirk. This is not simply in terms on the essential narrative, two women of different ages in love with the same, idealized, man. Also there is the consideration of how a filmmaker can simultaneously fulfill his artistic ideas while at the same time fulfilling the mandates of the studio, much like Sirk did, working on behalf of producer Ross Hunter and Universal Studios. This also is a reminder of some aspects of writing about films from other countries as there is less thought about the commercial or studio demands made upon a filmmaker. This is not to take Kenji Mizoguchi down a peg or two, but to note that he was no more an independent artist than peers like Sirk, Vincente Minnelli or Nicholas Ray.

The Woman in the Rumour is also an illustration of the gap between what filmmaker may express and their personal lives. Again, Tony Rayns introduction is helpful on that score. Foremost might be Mizoguchi's prickly relationship with prostitutes and actresses. When Rayns mentioned that Mizoguchi regularly went to the "pleasure quarters", I swore I heard the head of Herman G. Weinberg's ghost explode. Which reminds me, that I need to see Street of Shame again. At any rate, Mizoguchi, far from condemning prostitution, was only against women forced into the profession according to Rayns.

The character of the young doctor may be Mizoguchi's proxy, and again provides a mixed reading of the film. Yukiko discusses her education as a pianist, and mentions how women are generally less valued than men. Matoba presents himself as a more enlightened male, encouraging Yukiko to again pursue her musical ambitions, and at the same time explaining that the women who work for Hatsuko are not to be seen as victims. At the time the film was made, Kinuyo Tanaka, the woman who played Hatsuko, had also become Japan's first female film director. A frequently used actress in Mizoguchi's films, Mizoguchi attempted to use his influence to keep Tanaka from taking on a second directorial assignment. In addition to having a former muse become, to some extent, a competitor, I suspect Mizoguchi chafed at the idea of Tanaka taking on a project written by critical rival Yasujiro Ozu. The Woman in the Rumour was Mizoguchi's last collaboration with Tanaka.

In black turtleneck shirts, her hair pinned back in a boyish cut, and slender frame, Yoshiko Kuga, as Yukiko, made me think often of Audrey Hepburn or Jean Simmons. I've seen Kuga in other films, most notably Zero Focus, where she stars as the wife in search of a missing husband she barely knew. Coincidentally, Kuga starred in Kinuyo Tanaka's directorial debut, Love Letter. Kuga never became famous outside of Japan, and I wonder if it was because no one thought to exploit her similarity to Hepburn or Simmons. This still photograph indicates another side of Kuga that inspires a deeper look into her filmography. Tanaka might have played the title character in The Woman in the Rumour, but the film becomes Yoshiko Kaga's, especially in the final scene, when Yukiko cheerfully accepts her fate to follow in the path of her mother.

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 08:07 AM

August 03, 2011

Chikamatsu Monogatari

Crucified Lovers

Kenji Mizoguchi - 1954

Eureka! Masters of Cinema Region 2 DVD

I've been thinking more about filling in some of the gaps in my knowledge of Japanese films from the "Golden Age", that period that more or less begins with Kurosawa's Roshomon and faded away around the time of Red Beard. Seeing the Naruse films a little over a year ago has certainly been an impetus. My plan is to write about several films currently not available commercially as Region 1 DVDs during the month of August, discussing filmmakers who are considered classic, and those who have only recently been given greater consideration.

I'm not a big fan of Tony Rayns. I think he has taken on the role of cultural policeman, attempting to dictate which filmmakers are worthy of discussion. Nonetheless, his video introduction to Chikamatsu Monogatari is worth watching if just to learn about how Mizoguchi came to make what was essentially a studio assignment. And yes, even though Mizoguchi had a hand in shaping the screenplay, the film was essentially a job to do in between films of more personal interest. This also brings to mind some of what Andrew Sarris would discuss in his The American Film, that Hollywood directors, that the mark of an auteur was sometimes because of, as well as in spite of, the studio system.

Where Chikamatsu Monogatari fits in with other films by Mizoguchi is that peoples' lives are affected not by what they have done, but by what others assume they have done. The artisan and his master's wife are not lovers until after they run away from the false accusations about their relationship. Previous to that, we see Mohei, the house artisan in a print shop, scrupulously obeying protocol with Osan, the wife of his master. Mizoguchi often explored the theme of class differences, especially during the feudal period. Mohei's one relatively small lie, of using the master's seal to get a loan on behalf of Osan's spendthrift brother, snowballs into a situation that traps all of the principle characters, causing loss for everyone.

A sort of visual metaphor for the lack of control the characters have over their lives is illustrated in a seen with Mohei and Osan in a small boat. Osan has decided to commit suicide by drowning. Just before she takes the fatal leap, Mohei confesses his love for her. Osan declares that she want to continue living, even if it is on the run, with Mohei. The two embrace while the boat seems to drift with the current.

Kazuo Hasegawa was cast as Mohei, in spite of Mizoguchi's objections. I'm not sure why the perpetually baby faced Hasegawa was so popular, but at age 46, he was too old for the part. The casting of Hasegawa is no different from many other films with long in the tooth actors pretending to be much younger. By contrast, Kyoko Kagawa was just 23 when she performed the role of Osan, her second part for Mizoguchi following Sansho the Bailiff, also in 1954. Fans of Obayashi's House and that film's haunting hostess might want to note an early significant appearance by Yoko Minamida, seen here as a household servant in love with Mohei.

Even if Chikamatsu Monogatari is considered one of Mizoguchi's lesser films, there are still some visual moments to be savored. In addition to the drifting boat, there is a scene done as a single long shot, where we see Mohei brought down and tied by his pursuers, while Osan is seen locked into a small palanquin, and carried off away from the camera. Also, there is the shot of Mohei and Osan holding hands while tied together, content that they will be together in death if not in life.

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 08:47 AM

August 01, 2011

Final Take

Kinema no tenchi

Yoji Yamada - 1986

Panorama Entertainment Region 3 DVD

Filmed in between his regular assignments in the "Tora-san" series, Final Take is one of Yoji Yamada more personal films. The film is something of a love letter to home studio Shochiku, with nods to A Star is Born in its various tellings, a lightly veiled cinema a clef about Yasujiro Ozu, with a slight detour by way of Sullivan's Travels. There is the question I have to resolve regarding what seems to be missing from this DVD version as various sources state the running time is 135 minutes, while the Panorama DVD clocks in at 116 minutes. Possible missing scenes aside, the film is probably of most interest for this recreation of filmmaking in Japan in the early Thirties.

Koharu, a candy seller in a movie theater, is briefly interview by director Ogura, who thinks the young woman has the face and the voice to be a movie actress. What Koharu lacks, at least initially, is any sense of acting ability. After initial discouragement, Kohura slowly rises from extra work to small supporting roles, catching the eye of Ogura's assistant, Kenjiro. Dismissing the director's films as mere "flickers", Kenjiro aspires to make serious films addressing the issues of the day, a difficult proposition not only due to studio politics but the politics of Japan demonstrating its military strength. Koharu also faces trouble at home dealing with her alcoholic father, a former itinerant stage actor. The studio's main leading lady elopes just before filming commences on Ogura's next production, giving Koharu the chance to show her acting ability.

Yomada includes some scenes showing what it was like to see movies in Tokyo at the time, with the huge billboards, the hawkers outside the theaters encouraging pedestrians to see the currently showing film, and the candy sellers walking up and down the aisles prior to the film start. In what appears to be one of the classier theaters, a silent film is on display, with a benshi, looking like a professor at a lectern to the right of the screen, provides narration. One of the two big sets is a recreation of Asakusa, the part of Tokyo where most of the movie theaters were located. The other major set is a recreation of Shochiku's Kamata Studio. One of the main musical themes is the "Shochiku Studio March", which Koharu sings near the end of the film.

There are also several scenes of filmmaking which are not too different from what might be scene in other movies about making movies. The one scene that did catch my eye was of the Ozu stand-in, Ogura, filming a scene with the camera almost at ground level. There is also a comic scene of two lovers in period costume, drenched in what was ordered to be a light spring rain. Kenjiro writes what is intended to be a serious film about a young girl sold into prostitution, only to be distressed to see that the screenplay has been transformed into a nonsense comedy that takes part of the title and leaves the rest behind.

One of the subplots involves Kenjiro's friendship with a man sought after by the government authorities. It's the kind of subject matter Yamada was able to explore more fully in Kabei, almost twenty years later. The friend appears at Kenjiro's room to hide a small package, the contents which are never revealed. Kenjiro and his friend are arrested by police who have presumably trailed the friend. There is a comic moment when one of the detectives, notices that Kenjiro has a book about Marx, unaware that it is about the Marx Brothers. Kenjiro is locked up in jail after taking a beating, impressing his fellow inmates by being on speaking terms with a famous actress. Kenjiro is next seen returning to the studio, with Ogura asking if he had finished his writing assignment. It is this particular sequence that seems to have been abridged based on the published running time. The cut from Kenjiro in jail to his next returning to the studio seems very abrupt. It is in jail where Kenjiro gains a sense of value of "flickers" and making movies for the masses.

The final film within the film is titled Floating Weeds. That title, and the presence of Chishu Ryu in a small role, are the clearest links to Ozu. This is the kind of film that would initiate a guessing game for those with some knowledge regarding Japanese film history regarding who some of the other characters are modeled after. Also appearing are Tora-san himself, Kiyoshi Atsumi as Koharu's father, and Tora-san's sister, Chieko Baisho, as Kuharu's neighbor. As befitting a film about Japan's studio system, the director whom Yamada served as assistant, Yoshitaro Nomura, is credited here as the producer. The title has been translated as "Heavenly Cinema World", and the film release coincided with Shochiku's leaving Kamata for Ofuna. While the film was made at the time as a tribute to Japan's filmmaking past, in regards to Yoji Yamada's lengthy career, Final Take seems like an opportunity taken to touch on themes that would be explored again in greater depth, with fewer commercial or political restraints.

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 08:22 AM