« August 2011 | Main | October 2011 »

September 29, 2011

Black Sun

Kuroi taiyo

Koreyoshi Kurahara - 1964

Eclipse Region 1 DVD

Black Sun isn't a sequel to The Warped Ones, but it does continue some of the themes, and even reuses one of the settings. It's also, at least for me, a difficult film to get a handle on. I'm not sure about what Kurahara is trying to say about race and religion.

Tamio Kawachi returns as the young jazz fanatic, Mei, a less animated version of the character he played in the earlier film. Stealing enough wire to get cash for the Max Roach album, Black Sun, he no sooner steps out of the record store only to have it dropped on the street when he's almost hit by a car. The high heeled female passenger blithely steps on the album, breaking it. The driver gives some money to Mei as payment. As far as Mei is concerned, the cash isn't enough, and he steals the couple's car.

Not getting ready payment from a fence, Mei is given an old beater to drive in the interim. The car is so slow that bicyclists complain about Mei getting in the way. Mei stops in the street due to a crowd gathered to see a soldier, part of the U.S. occupation troops, pulled out of a river. The military police warn about a fugitive soldier on the loose with a machine gun.

Mei is squatting in a bombed out church. It's also where the fugitive, a black G.I. named Gil is hiding. While using the same actor, Chico Roland, and the same character name as in The Warped Ones, the similarity ends there. Gil has a bullet wound in the leg. Akira is oblivious to Gil's physical pain, instead overjoyed at the presence of a black American in his life. And at this point the film raises lots of questions for me.

Mei only understanding of black America is through music. Posters of various musicians cover his walls. His dog is named Thelonious Monk. As far as Mei is concerned, Gil should be able to play music and sing for him. Gil tries to control the situation with his machine gun. Aside from the language barrier, the two men battle for control over each other while simultaneously trying to elude the law. More questionable is a scene where Mei paints Gil white, and displays him to his friends at the jazz club, the same one seen in The Warped Ones, as his slave while Mei goes out in blackface.

And maybe I am misreading Kurahara's intentions here, especially watching a film almost forty years old, and yanked from some of its cultural contexts. What I am seeing is a study about how "the other" is made to be exotic, to be idealized. And it could be something I may well be guilty of as well. What Black Sun presents is such an idealization in extreme, as well as its opposite, when Mei humiliates Gil, again devoid of really understanding the implications of his actions from the point of view of a black American.

In this same way, I am also not certain what Kurahara is trying to say about Christianity. There are several shots of Gil's crucifix. At one point Gil prays to one of the ruined church statues. There are also other shots of religious symbols within the church Gil and Mei hide in, as well as another church Gil sees when the pair are on the run. The symbolism at the end of the film, where Gil literally ascends to the heavens is open to interpretation.

The music for the jazzy scores for Black Sun and The Warped Ones have been recently made available on CD. Certainly, Kurahara has been musically aided by Toshiro Mayuzumi, as experimental in his soundtracks as Kurahara has been in his filmmaking.

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 08:53 AM

September 27, 2011

The Stool Pigeon

Sin yan

Dante Lam - 2010

Well Go USA Region 1 DVD

An almost visual constant in The Stool Pigeon is the lack of space. Streets and alleys are narrow, with only room to run forwards or back, often to an enclosed space. Even when there is the rare shot of sky, it is surrounded by the skyscrapers of Hong Kong. The effect is like watching people running through a maze, only more deadly. The sense of physical enclosure is also stressed with characters inside cars, hiding within the cramped spaces of a street market, and in an abandoned classroom stuffed with chairs. For Dante Lam, there is no escape, whether from cops, crooks or karma.

Even though Nick Cheung is top billed, the film firmly belongs to Nicholas Tse in the title role. Recruited by Cheung to infiltrate and rat out a criminal gang, Tse is the pivotal one in the action scenes. And what action! First up is a street race where Tse has to prove he has the goods to be a getaway driver, with plenty of high powered cars. Even better is when Tse, choosing not to deal with a police roadblock, careens away amidst heavy daytime traffic and police pursuit while Dean Martin croons "White Christmas". Yes, the film takes place around Christmas time in Hong Kong, providing some holiday cheer for those who want decisive break from It's a Wonderful Life. There is also the big jewelry store heist, where Tse smashes his car through the store. Finally, there is the breathless street chase with Tse and Kwai Lun-mei pursued by the gang that they have betrayed. Tse also has the best name for a character, Ghost, Jr.

As the police detective who works with informants, Nick Cheung's character is forced to be sidelined by the energy of Tse. Cheung's character, Don Lee, is essentially passive. Making arrangements, meeting with the "stoolies", Lee watches the action from a safe distance. It is only near the end of the film that Cheung takes action himself, when there is no else around. While one of the subplots attempts to detail Detective Lee's sense of emotional distance from the people he works with, his attempts to reconnect with his ex-wife who has forgotten him due to a traumatic injury seems out of place with the rest of the film. The attempt to humanize Lee not only disrupts the pacing of the film, but shoehorns a very contrived situation that distracts from the rest of the drama.

Better is watching the relationship unfold between Nicholas Tse and Kwai Lun-mei. In a humorous flashback, we see the two crossing paths, when he's chased by cops, and she, by a criminal gang, only to escape when the cops choose to chase the gang. Kwai's role as Dee, along with Ghost, Jr.'s sister, provide a narrative thread concerning the commodification of woman, as both are used for their financial value to others, with money used to purchase freedom.

I have to admit to being more conscious of how the action sequences were filmed after reading a series of essays by Jim Emerson. Then again, I wasn't watching in slo-mo or frame by frame, but appears that Lam and company have adhered to the classic rules of keeping the sense of space and direction consistent when cutting between characters. The action is truly fast and furious, but it doesn't look edited in a cuisinart. There is plenty of blood, bullets and bandages by the time the closing credits roll. It's also probably the only movie made where a criminal couple cases a jewelry store, and then takes a moment to have their photo taken with Santa Claus.

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 07:15 AM

September 25, 2011

Coffee Break

Michelle Pfeiffer in Cheri (Stephen Frears - 2009)

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 08:57 AM

September 22, 2011

I Hate but Love

Nikui Anchikusho/The Despicable Guy

Koreyoshi Kurahara - 1962

Eclipse Region 1 DVD

A good chunk of I Hate but Love is devoted to a road trip from Tokyo to Kyushu, a 900 mile drive. The film seems to periodically meander, lose direction, and regain some momentum, just like the main characters. The film is centered on a radio and television personality, Daisaku, and his manager, Noriko. The film is something of an examination of the meaning of love and celebrity, with two of Japan's biggest movie stars of the time, Yujiro Ishihara and Ruriko Asaoka.

Visually, it veers between Korehara's freewheeling shots with the camera spinning on its axis, or lots of hand held, documentary style shots on the streets of Tokyo, Osaka and other points, with scenes composed of shots where the camera never moves. Part of the story is about Daisaku driving an old jeep to Kyushu on behalf of a young woman who's maintained a platonic love affair with a young doctor in a remote village, their relationship fueled by their exchange of letters. There is discussion as to whether Daisaku is driving the jeep as a publicity stunt or as a humanistic gesture. There are several scenes of crowds on the street gathering in front of Daisaku and the jeep, but they could well have been in actuality shots of fans gathering to catch a glimpse of Ishihara. Had an American producer seen this film when it was released, I'm sure he would have had the idea to do a remake starring Elvis Presley.

According to Mark Schiling, in his book on Nikkatsu films from the late Fifties and early Sixties, the original English language title was "That Despicable Guy". I'm not sure if despicable is quite the right word to describe Daisaku, but I like that title better. From the opening scenes, it is evident that Daisaku is tiring of the demands of his schedule of radio banter, talk show appearances, and late night appearances at night clubs. All the guy wants to do is sleep. Noriko has Daisaku's every day, and virtually every hour planned out in advance. Adding to their tension of the business relationship is their personal relationship where love is kept at a distance, both fearful of how it could affect their careers. When Daisaku takes off to drive the jeep, Noriko sees the professional commitments coming apart, threatening the careers of both of them.

Ishihara, also popular as a singer, is given a couple of opportunities to sing, both on and off the camera. I am assuming here that Korehara was permitted some freedom as a filmmaker, with such signature motifs as shots directly of the sun, and some rain drenched moments. But the film mostly was designed to serve as a vehicle for the two very popular stars. What may be amusing to contemporary audiences, that may have caused young Japanese girls and boys to swoon when the film came out, are the several scenes of the Ishihara and Asaoka in their underwear. Ishihara has a couple scenes wearing nothing but his tighty whities. Asaoka is seen in her white bra and granny panties, at one point admiring herself in a full length mirror. Aside from the display of celebrity skin, the film indirectly expresses Ishihara own evolution from studio contract player to independent star.

The film is also something of an odd choice in the Kurahara series. Not having seen Kurahara's other Nikkatsu film but relying on descriptions as well as the trailer, I would have preferred Glass Johnny: Look like a Beast. Having seen I Love but Hate, I would also like to see the previous film Kurahara made with Ishikawa and Asaoka, Ginza Love Story. Of possible interest to some might be the Toshiro Mifune vehicle, Incident at Blood Pass with Ishikawa and Asaoka in supporting roles, filmed eight years later. By this time, Yasujiro Ishikawa's alcoholism had physically taken a toll on the former teen idol, his puffy features almost making him initially unrecognizable, and saddening when Mifune refers to him as the "young fellow".

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 06:08 AM | Comments (2)

September 20, 2011

The Warped Ones

Kyonetsu no kisetsu

Koreyoshi Kurahara - 1960

Eclipse Region 1 DVD

Did Koreyoshi Kurahara and his scriptwriter, Nobuo Yamada see Godard's Breathless prior to making The Warped Ones? Godard's film opened in Japan in March 1960, while Kurahara's film debuted the following September. A six month gap between the two films would be considered fast but not impossible, and definitely not that unusual back at that time. There seems to be an influence, not only in filming in the streets of Tokyo, but in the choice of characters.

Kurahara's main character, Akira, makes Godard's Michel seem almost like a model of decorum in comparison. First seen busted for grabbing the wallet of a bar customer, part of a scam with his young prostitute girlfriend, Yuki, Akira is sent to a juvenile prison where time is passed by getting into fights. Released from the joint, Akira and pal, Masaru, dive back into the life, stealing knives and a car, picking up Yuki, and heading out to the beach. At the beach, the guy who set up the bust, Kashiwagi, is seen, and knock over when Akira drives by with his car door open. The gang grabs Kashiwagi's girl, Fumiko, who unwillingly becomes part of Akira's life.

What impresses about Akira, as played by Tamio Kawachi, is his almost unflagging exuberance. When he and Masaru first enter the streets from prison, they sound like Beavis and Butthead, yipping and grunting to each other in enthusiasm to being out in the sun. One of Kurahara repeated visual motifs is shots of the sky, oven too brightly lit and overexposed. Akira ferociously dives into food and drink like an animal, and emotionally dives into jazz to the exclusion of his surroundings. Akira doesn't just taste life, but gobbles it up whole and spits out what doesn't satisfy him. The opening of the film are dizzying shots of the ceiling of Akira's favorite bar, with its photos of various American jazz musicians, with Kurahara duplicating the effect of looking closely at a record spinning on a turntable.

There is no explanation for Akira's amorality, and even when he seems to be taking responsibility for his actions, it still comes across as making a bad situation worse. Akira's love of jazz, specifically jazz by black American musicians, seems emotionally rooted, as is his friendship with Gill, seemingly based on his personification of the only art form for which Akira feels any affinity. Part of the film deals with Akira's conflicting relationship with Fumiko, an accomplished abstract painter. Akira goes to an exhibition where he is bemused by what he sees, going as far as turning one painting upside down to the approval of one of the other gallery patrons. Later, crashing in on a party at Fumiko's house, Akira is introduced as a model, but is indifferent to the intellectual and hipster approval of his anti-social behavior. Akira's life seems to be as improvised as the music he loves. At the same time, Akira is oblivious to how is life is connected to others, or the formal underpinnings of jazz, only seeing it as a musical form that as he explains was created in America by black musicians, stolen by white musicians, and copied by Japanese.

Kurahara's camera is just as restless as Akira, almost constantly in motion. Many of the street shots have a documentary quality. A glanced sign would indicate that the bar where much of the film takes place was in Shibuya. Fumiko's house seems to be in an outer section of Tokyo, where has a small chicken coop in the back. This is a Tokyo that existed fifteen year following the end of World War II, but not yet the overly developed urban Tokyo of today. Seen within the context of traditional Japanese behavior, Akira must have been extremely shocking to audiences when the film was first released. The Japanese title has been translated as "Season of Heat". The English language title ultimately refers to all of the characters, as Fumiko and Kashiwagi turn out to be as warped as Akira, Masaru and Yuki.

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 06:57 AM

September 18, 2011

Coffee Break

James Arness and Michael Emmett in Gun the Man Down (Andrew V. McLaglen - 1956)

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 05:57 AM

September 15, 2011

Intimidation

Aru kyouhaku

Koreyoshi Kurahara - 1960

Eclipse Region 1 DVD

I'm not alone in enjoying the use of close-ups in films. The classic example for some critics and historians is Dreyer's Passion of Joan of Arc. Andrew Sarris has cited Sam Fuller's use of close-ups in I Shot Jesse James. Sergio Leone's close-ups are also famous. What we're talking about here are not just shots where the face fills the frame, but also shots of the eyes, maybe the lips, the wrinkle of the brow, the facial tic.

A good portion of a robbery sequence in Intimidation is made up of close-ups. Koreyoshi Kurahara cuts to the glancing, nervous eyes of the robber, his face mostly covered by a scarf and hat. The bank employee fear is more obvious. Both are sweating. The scene could well be Koreyoshi's attempt at doing something along the lines of the heist in Riffifi. There is no dialogue, but instead the exchange of nods and glances. Kurahara's robbery is nowhere near as long as the one filmed by Jules Dassin, but I would not be surprised if the older film did influence Kurahara, an admitted Francophile, who probably saw the film a year or so before his own directorial debut.

There are only three main characters: a thug who shows up at a small town to blackmail an assistant bank manager, the assistant bank manager who is getting ready for a promotion to manager at another bank, and a clerk who began his career at the same time as the assistant manager, a long-time friend for whom career advancement may never come. The film could be read as a look at Japanese society, where advancement is only possible by family connections, taking advantage of other people, or using various illegal means. The intimidation comes from the flow of power between the three characters here, each one getting getting the upper hand on the other, and how they use that power. All three men find themselves in situations where they feel helpless, reduced to begging for their lives.

As the assistant manager, Nobuo Kaneko looks like the kind of guy who never missed a meal in his life. Looking entirely self-satisfied, whether getting a promotion at a relatively young age, or finding that his old love, and best friend's sister, still pines for him, Kaneko has the appearance of a guy for whom getting kicked in the ass by life, actually his own misdeeds, could never come soon enough. Kojiro Kusanagi as the blackmailer looks lean and hungry. What struck me about his appearance most was his very small mouth, perhaps appropriate for one who only says what is most necessary. The real star would be Akira Nishimura as the milquetoast bank clerk whom no one takes seriously. If I hadn't had the notes that come with the DVD, I would have referred to him as THAT GUY, you know the kind of creepy guy who appears in a bunch of Akira Kurosawa movies.

Part of the fun of Intimidation is that it provided the three, who would have supporting or minor roles in much more famous films, with the chance to be the main stars. Nikkatsu Studios resident bad girl, Mari Shirakai puts in slightly more than a token appearance as the sister of the bank clerk, ashamed of the failings of her brother, but not too ashamed to throw herself at her now married former lover. The DVD is part of Eclipse's new five disc set of film by Kurahara. I hope to cover the other films in the coming weeks.

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 08:55 AM

September 13, 2011

The Exterminator

James Glickenhaus - 1980

Synapse Films Region 1 DVD

That they don't make films like they use to can certainly be applied to The Exterminator. The film is another example of the kind of productions made on relatively modest budgets that were all but extinct when Hollywood films became competitors for opening weekend grosses playing on several multiplex screens around the U.S., and eventually the world, at the same time. What is also more of a present day anomaly is seeing movies about working guys that is neither condescending to the men or their work.

I think that it's the attitude that James Glickenhaus has towards his main characters that made The Exterminator a popular, if not critical success. It was that the sense of recognition that some of the people on the screen had daily lives not too different from those in the audience. In his commentary, Glickenhaus talks about how his film was playing to full houses in two New York City theaters, the Lyric on 42nd Street, and the National Theater. I've been two both theaters, and could imagine people whooping it up when Robert Ginty takes on the various bad guys. The National was a first run theater that mostly showed action movies on what I believe was the biggest screen in town, which would make the several explosions quite overwhelming. Sure, the film is a revenge fantasy, but this was a film made mostly for people who saw life as an everyday struggle just to get by, with a hero who could just as well have been a beer drinking buddy.

The film immediately jumps into the action with a scene in Viet-Nam. Robert Ginty and Steve James are both prisoners of the Viet Cong. James is able to undo his ties and overpower one of the soldiers. Ginty gets shot but is saved by James, pulled onto a helicopter. Cut to New York City where the two are working at different parts of a food distribution center. Ginty catches some young thugs breaking into one of the storage rooms where they're stealing cases of Rheingold beer. But it's James, who's the one who kicks ass here. The thugs, a bunch of young white guys who are part of a gang called the Ghetto Ghouls, later catch James alone, beating him up and leaving him paralyzed. Ginty finds the gang's hideout, killing a couple of the members. One of the Ghouls remarks of James that he is, "just a nigger". Ginty's priceless response is, "That nigger was my best friend, motherfucker!".

I don't believe that Glickenhaus intended The Exterminator to be understood on a literal level. His version of New York City melds parts of the Bronx with Brooklyn. Likewise, the Ghetto Ghouls party in a room decorated with posters of Che Guevara and Angela Davis, low level career criminals who might not necessarily be capable of articulating a political position other than being grabbing images and iconography that would be considered anti-social and/or anti-establishment. Later, when detective Christopher George checks out Ginty's apartment, he notices a copy of Jean-Paul Sartre's The Condemned of Altona. Glickenhaus briefly discusses why the book is used. While there are no philosophic discussions in The Exterminator, on its very visceral level, it also is about personal and public responsibility, and the uses of violence as means to an end. The use of the book also serves to indicate that Ginty's character is a person of some education and intelligence who works at a meat packing plant maybe more by circumstance than by choice. In The Exterminator, almost everyone is working for someone else. The difference between the good guys and the bad guys is one of choices made, knowing that there is little to control when financial or political power are always in the hands of someone else.

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 05:57 AM | Comments (1)

September 12, 2011

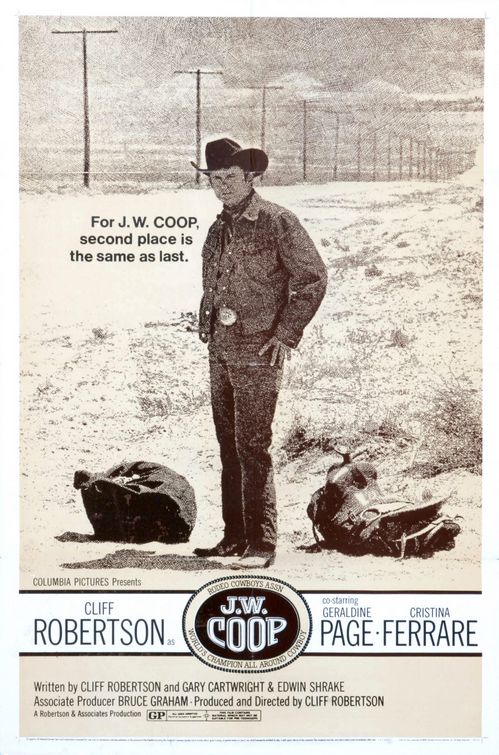

Cliff Robertson: 1923 - 2011

It may be hard for some to believe, but there was a time when movies about rodeo cowboys were considered a viable genre. J. W. Coop came out in 1971, during a brief moment when movie goers could also see Sam Peckinpah's Junior Bonner and James Coburn in The Honkers, a film that was something of a remake of Nicholas Ray's The Lusty Men. I was able to attend an advance screening of J. W. Coop with Cliff Robertson in attendance. I don't remember too much about it except that I liked the film, and that Robertson was gracious about my praise for Too Late the Hero, a film I only found out later was made with neither Robertson or director Robert Aldrich enthused about a second collaboration following Autumn Leaves. Robertson was able to use his short-lived post Oscar clout in order to make J. W. Coop his way.

Some of my favorite films starring Robertson are not ones that he necessarily thought were good, or perhaps representative of his best work, but instead represent a personal, and chronological, top ten from a career that spanned almost fifty years.

1. Picnic (Joshua Logan - 1955)

2. Autumn Leaves (Robert Aldrich - 1956)

3. Underworld, U.S.A. (Samuel Fuller - 1961)

4. My Six Loves (Gower Champion - 1962)

5. 633 Squadron (Walter Grauman - 1963)

6. Charly (Ralph Nelson - 1968)

7. Too Late the Hero (Robert Aldrich - 1970)

8. J. W. Coop (Cliff Robertson - 1971)

9. The Great Northfield, Minnesota Raid (Philip Kaufman - 1972)

10. Obsession (Brian De Palma - 1976)

Also, two favorite television appearances: The first episode of The Outer Limits - "The Galaxy Being", and from The Twilight Zone - "The Dummy".

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 07:30 AM

September 11, 2011

Coffee Break

President Hathaway in Monsters vs. Aliens (Rob Letterman & Conrad Vernon - 2009)

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 10:34 AM

September 08, 2011

Shaolin

Xin shao lin si

Benny Chan - 2011

Well Go USA theatrical release

There's a scene in Shaolin where several Buddhist monks are standing on one leg, holding the other leg up, while maintaining their balance on tall posts with space for one foot. The scene is emblematic of Shaolin as a whole in that narrative is a balancing act between martial arts spectacular and Buddhist parable. The scene in mentioned here is also quite funny as one of the monks, hungry for a meal, pretends to be eating. This leads to a discussion of how to act as monk when one is surrounded by warfare and famine. Some of the monks jokingly, perhaps, discuss becoming outlaws, and several fall from the posts they are standing on, losing their concentration to laughter. From a Buddhist point of view, the scene is an illustration of the conflict between having an elevated life condition when the more human needs bring us down to earth.

I have to admit that as a Buddhist, I'm going to bring my own interpretation of certain aspects of the film. Is an understanding of Buddhism or Chinese history needed to enjoy Shaolin? Probably not, although I would think it would help in understanding some of the motivations of the characters. Certainly it's a handsomely produced film, and although Benny Chan is the director of record, credit needs to be given Corey Yuen as action director, and a frequently estimable director in his own right. At a time when various critics have been discussing how action sequences are filmed and edited, especially in Hollywood films, Yuen shows how to use space and action effectively to follow the chaos, especially in the big battle scene, where monks are fighting Nicholas Tse's army, and a small foreign army is shooting cannons at the temple.

Taking place during the 1920s, Hou, a general leading one of the conflicting private armies, chases an enemy general to the Shaolin temple. After promising the temple's abbot that he will allow his wounded enemy to live, Hou shoots the man, and defaces the temple's sign. Accompanying Hou is Cao, an ambitious lieutenant. When Hou is given the opportunity to get a large shipment of machine guns from an unnamed foreign government, in exchange for that government's right to build a railroad, he rejects the offer in the name of protecting Chinese sovereignty. Planning a dinner in which to ambush a rival general, Song, Hou finds himself ambushed by Cao, losing his wife and daughter. Hou finds himself at the Shaolin temple, initially as sanctuary. Choosing to become a monk, Hou faces the effects of his past actions, his karma as it were. Even when given the chance to reunite with his wife, Hou stays at the temple for the inevitable confrontation with Cao.

Still, it would be the comic moments of Shaolin that would be best remembered by me. One very obvious joke would be having Jackie Chan, playing the temple cook, declare to a soldier that he does not know kung fu. Jackie Chan then proceeds to do what he does best, which is kick butt using every available prop and even people as a tool for fighting. Chan looks visibly aged, and the role may be his way of letting the audience know that he can't continue to do the kind of physical performance that could be sustained for an entire feature. Nevertheless, when he fights soldiers who have come to destroy the temple, his action scenes are pure vintage Jackie Chan from his best Hong Kong films.

The film is primarily dominated by Andy Lau, as Hou, an actor I've found to be more interesting as he has gotten older. One of the aspects to his career that makes Lau interesting to watch is his fearlessness in taking on roles that are not always heroic, nor reliant on what were his pretty boy looks of the past. Fan Bingbing appears as Hou's wife, a role that doesn't give her as much of an opportunity to show her range as in the recent Buddha Mountain.

There are hundreds of extras, swords, guns, and explosions, but some of the best parts of Shaolin are those that are smaller, more intimate. Who's not going to laugh when a young acolyte bonks a soldier on head with a frying pan, and then makes a small prayer over the unconscious man? And, yes, the symbolism is pretty obvious, but one of the more potent images is that of Andy Lau falling into the hands of the giant Buddha.

All photos courtesy of Variance Film/Well Go USA

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 08:13 AM

September 06, 2011

Triad Underworld

Jiang Hu

Wong Ching-po - 2004

Palisades Tartan Region 1 DVD

I know it wasn't everyone's cup of chai, but I was one of those people saddened by the demise of the Tartan DVD label. Sure, they focussed on certain kinds of films, but the Tartan Asia Extreme label was how many of us were introduced to Park Chan-wook, Shinya Tsukamoto, personal favorite - the Pang Brothers, and other Asian filmmakers of varying repute. I even saw every Tartan Asia Extreme DVD in the Denver Public Library. Since the closure of the original company, many of the original titles are available again through Palisades Tartan. The new DVD, Triad Underworld seems to indicate that the new company is picking up where the original Tartan left off.

The stylization barely hides a relatively simple story. Two young punks, looking to make their reputation as Hong Kong gangsters, make their way through the streets on the way to kill an established gang boss. Their target, Hung, has just become a father. While young Yik and Turbo weave in and out of back streets and alleys, Hung and his best friend, Lefty, discuss Hung's possible retirement from criminal life. Cutting between the two sets of friends, the film establishes the parallels between Yik and Turbo, and the days when Hung and Lefty first made names for themselves.

I don't know if Wong Ching-po as seen the films by Gaspar Noe, but visually there are similarities. The opening shots track through a restaurant as the staff cautiously walks around Edison Chen, the volatile Turbo. Claustrophobic nightclubs crammed with kids dancing also makes me think of Noe, as do shots of large, empty urban environments such as warehouses and tunnels. During one scene, Hung and Lefty are eating dinner in Lefty's restaurant, and Wong cuts between the two, with the background in continual motion, indicating the lack of stability in the relationship between these two longtime friends. Again like Noe, Wong is interested in creating visual equivalents to ever shifting senses of self.

Even though Andy Lau is one of the producers, his own role is the less showy Hung. The more dramatic appearances are by Jacky Cheung as the dreadlocked Lefty, with Shawn Yue as Yik. Virtually axiomatic in a Hong Kong gangster film is an appearance by Eric Tsang, with the five foot four inch actor playing a mob boss named Tall Guy. Johnny To mascot Lam Suet is briefly seen as a hapless cop who's lost his gun to Yik and Turbo.

Although he's yet to make his reputation internationally, Wong Ching-po was awarded Best New Director for the Hong Kong Film Awards in 2005. I should also note that Wong's newest film, Revenge: A Love Story has been getting attention at the festival circuit. Triad Underworld was also nominated for costume design and art direction, fitting for a film that stronger in style than substance. The strongest dramatic moments are part of a subplot involving Yue going on a brief crime spree of several convenience stores to get enough cash to redeem his would-be girlfriend from a life of prostitution. Lin Yuan displays more spunk and energy as the prostitute named Yoyo than any of the guys that I had wished she had more scenes. Another very nice moment is when Yoyo writes her phone number on Yik's back, and in time honored movie tradition let's him know that she'll be waiting for him when he completes his mission. This is the first film I've seen by Wong Ching-po, and given the opportunity, not the last. The visual bravura makes Triad Underworld worth watching, even though it doesn't do enough to hide a familiar story.

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 08:06 AM | Comments (1)

September 04, 2011

Coffee Break

Collette Wolfe in Observe and Report (Jody Hill - 2009)

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 08:30 AM

September 01, 2011

Attack the Block

Joe Cornish - 2011

Screen Gems 35mm film

There is a shot in Attack the Block of a young man hanging outside his apartment building, holding onto the British flag, the Union Jack. The young man, pointedly named Moses, has trapped the alien creatures in his apartment, jumped out the window, and his holding on for his life. Especially in light of the recent riots in England, the symbolism shouldn't be missed. Certainly, Attack the Block can be enjoyed simply for its surface pleasures of resourceful kids versus creatures from outer space, but there is more to it than that.

The kids in fact live in what the British call council flats. Poor, mostly black, and casually criminal, these are not the youth idealized in something from Steven Spielberg. One of the more interesting choices Joe Cornish has made is to break from the standard science fiction narrative where the characters are usually white and more or less middle class. Nor is there a scientist in the bunch. The closest there is to someone with a modicum of scientific knowledge is a stoner who may have understood that what may be happening is, at least in intention, hardly an alien invasion. Cornish also does something radical in his introduction of the kids to cause them to work to gain the sympathy of the audience.

The action takes in and around one of the council flats where the boys live. The one young woman who joins them, only because she sees it as the only way to survive, is named Sam. While Attack the Block does not recall Howard Hawks in the same way that the films of John Carpenter do, there are some parallels to be found here. Most significantly is that Cornish centers his film on a small group that has to take on an outside force that is bigger and more powerful, and can only rely on their own abilities. Any additional help would be too late, if it came at all. By having the female character named Sam, it announces that at least during this situation, she is one of the boys, and entitled to take action along with the others. What makes this different from a Hawks film, or even a Carpenter film, is that Sam is a woman, while the boys are just that, boys, who are stumbling in their efforts to establish themselves as men.

There is no simple description for the space monsters other than, as the boys do, describe them as resembling a combination of bear, gorilla and wolf. In full shots, these creatures made me think of the unholy spawn of the titular Alien and Oscar the Grouch. Their most noticeable feature is their double set of sharp, phosphorescent teeth. Cornish has learned the lessons from the better recent creature features, like Alien and Pitch Black, so that what is seen of the creatures is mostly some very quick shots where we don't see much, but we see enough to put the audience on edge. The action takes place in a building called Wyndham Tower, perhaps named after the British science fiction writer, notably of Day of the Triffids, where alien creatures act less out of deliberate malice than from biological imperative.

But back to the boy and the flag . . . Attack the Block is about territory, or at least the illusion of territory. Moses and his gang act in their own misguided way in the name of their building and neighborhood when they are first introduced. A drug dealer in the building claims ownership regarding criminal activity when he recruits Moses to work for him. The police, when they appear, are there on behalf of the state to primarily keep those people that might grudgingly be called citizens in their respective places. The alien appear in this out of the way part of south London based also on a territorial claim that may have been in intention once it is established that the creatures are acting on animal instinct. Ultimately, Moses learns the hard way that actions have consequences, and takes a few steps towards a kind of adulthood that exists on other planet than the one inhabited by the cuddly kids and aliens in a Spielbergian universe.

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 08:22 AM