« December 2011 | Main | February 2012 »

January 30, 2012

The Cinema of Hong Kong

The Cinema of Hong Kong - History, Arts, Identity

Edited by Poshek Fu and David Desser - 2000

Cambridge University Press

I have mixed feelings about this collection of essays on Hong Kong cinema. Part of it stems from reading academic dissertations. As David Bordwell proves time and again, you can be academic without writing like one. Strangely enough, the most academic of these essays is also the one with a small filmography of cited films. I'm not enthused about books on film that are skimpy in illustrations and lack some kind of filmography for future reference. I also had mixed feelings about getting this particular book because, while I wanted some greater knowledge about the history of Hong Kong film, it seemed that one published over ten years ago might not be the best source.

What some of the essays helped me understand was not only a bit more about the history of Hong Kong film, but also the history of Hong Kong. In terms of film history, it helps put in a new perspective, at least for me, what is currently happening in Hong Kong cinema. What I have come to understand is that the tug of war between Mandarin and Cantonese dialect forces has been constant part of that history. Why that is important is that it puts the current challenges for Hong Kong filmmakers as part of continued shifts in what has, and what will, define Hong Kong cinema.

It is from this perspective that one can understand how commercial forces, meaning those of mainland China, have achieved for now, what cultural and political forces tried to achieve in the past. The Hong Kong cinema that gained international attention in the Eighties and Nineties, was primarily Cantonese. The filmmakers identified themselves as being part of Hong Kong, rather than part of the diaspora that left the mainland, or identified themselves as part of mainland China. In the years since Fu and Desser's book was published, the Hong Kong film industry has become a shadow of its former self.

What is happening currently might be described as another transitional stage regarding national and cultural identity. To take two of the most famous examples, John Woo and Tsui Hark, both now make films primarily for the mainland China market, allowing themselves the greatest commercial viability. Ann Hui and Edmond Pang, at least for now, are still specifically Hong Kong based in both subject matter, language, and especially in Pang's case,with Dream Home, making films that can not be shown in the mainland. Johnny To appears to be in both camps, between the Hong Kong gangster films that have made his reputation, and also making the kind of romantic comedies that are one of the two most popular genres in mainland China. (The other genre, if you haven't guessed, would be the costume epic.)

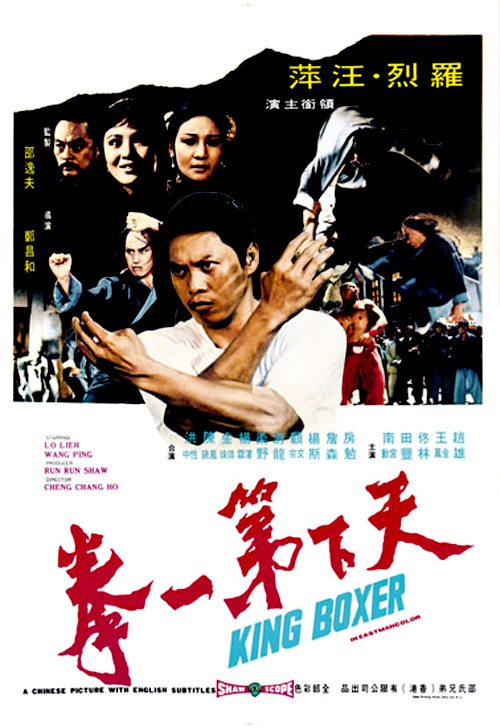

As for individual essays, David Desser discusses some of the history of Warner Brothers and the martial arts genre, including the development of the television series, Kung Fu, and the release of Five Fingers of Death (King Boxer), the first Hong Kong film to be distributed by a Hollywood major. There is also some explanation regarding why the martial arts films from Hong Kong were embraced by black urban youth. Maybe he felt it was unnecessary, but Desser does not mention how Warner Brothers had hoped lightning would strike again with another Asian genre, until The Yakuza failed at the box office.

Astonishing to read is Law Kar's chapter on how some of the films made in the Thirties, were produced in the United States, with Hong Kong immigrants on both sides of the camera, primarily in San Francisco. Also relayed is the story of Esther Eng, actress turned director, who made nine features, all thought to be lost. Eng's personal life seems just as colorful, as it turns out that bedding leading ladies was not just the province of male directors.

Seeing the films is another matter as much has been lost over the years. While most of the the films discussed from the Eighties onwards are easily available on DVD, it's the earlier films that require a bit more detective work, and often a region free player, in order to be viewed.

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 08:15 AM

January 29, 2012

Coffee Break

Istvan Lenart in The Man from London (Bela Tarr & Agnes Hranitzky - 2007)

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 08:32 AM

January 26, 2012

Wind Blast

Xi Feng Lie

Gao Qunshu - 2010

Mega Star Region 3 DVD

Wind Blast starts off with a point blank shooting in Hong Kong before jumping to a SUV speeding along on what passes for a highway, somewhere near the China-Mongolian border. For those who demand introductions and exposition, this isn't the film for you. There's no hesitation as the film dives into the action, eventually revealing a story about a trio of cops pursuing a hit man, who is also pursued by a pair of assassins.

What makes Wind Blast of interest is that it takes much of the iconography of the western and transposed it to contemporary China. This is not just in terms of the narrative, or that two of the main characters wear cowboy hats. The environment acts as an additional character as well. Much of the film takes place in an uninhabitable landscape, where desert meets mountain. Some of the characters are almost literally swallowed up by this environment with part of the film taking place inside an underground cave.

The wide open spaces allow for some very fancy driving between two dueling SUVs, as well as an SUV and a very large truck, combined with the tossing of Molotov cocktails. Traditional gun fights alternate with some high kicking martial arts. The climax takes place in an almost abandoned outpost of crumbling office buildings planted in the middle of nowhere. The western element takes over with a stampede of what appears to be hundreds of wild horses galloping through the town and into the main building where the police nominally are in control. As if that wasn't enough, dynamite is casually tossed back and forth between the police and lead bad guy, Francis Ng. The strong winter winds are the least of anyone's problems here.

The visual elements will recall for some Sergio Leone primarily, but also William Wyler and Delmer Daves. There are several shots of the mountains and desert, as well as shots of the characters dwarfed and overwhelmed by the vastness, the sense of endless space. The opening shots are of Hong Kong's skyscrapers. I name the three filmmakers because of how important geography is, as a part of their respective narratives, and how nature is perhaps not so much hostile, but indifferent to the conflicts of the characters. On top of that is a contemporary music score with Mandarin rock and rap, as well as harmonica. The title translates as "West wind martyrs" which is something of an exaggeration as it would suggest that almost everyone dies in this film. That the assassins carry computers with high tech GPS devices also pushes some of the plausibility. Such quibbles are easily put aside for the sheer visceral audacity of Gao and action director Nicky Li.

The best known cast member would be Francis Ng. The film belongs to Duan Yihong as the grizzled sage leader of the police force. Cowboy hats worn by Ng and Duan serve as both character and cultural signifiers well before either of them start shooting their guns. Duan, more than anyone else, is the equivalent of the archetypical character of classic Hollywood westerns. Also of interest is Yu Nan as a female assassin. Known best by some as the title character in Tuya's Marriage, but also with Speed Racer as part of her resume, Yu has been tapped to be in The Expendables 2. One look at Yu's bruised face, and "don't fuck with me" glare, should answer any questions as to her ability to hang out with Stallone and company.

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 08:34 AM

January 24, 2012

Red Eagle

Insee Dang

Wisit Sasanatieng - 2010

Shengchi Region 3 DVD

As almost any filmmaker can tell you, critical acclaim can only get you so far. And for all the attention and acclaim given to Wisit, the films he has made previously, even the internationally distributed Tears of the Black Tiger, were never financially successful. His newest film, hoping to capitalize on the love of the original Red Eagle series of films, was so hampered by artistic compromises that Wisit had temporarily considered leaving filmmaking. As it turned out, Red Eagle was another film mostly well received by Thai film critics, but again falling short commercially. Wisit has been working on another film though, this time independent of any studios.

I had written about the last film of the original series a few years ago. Sadly, of that was the only film available as a subtitled DVD. It perhaps made more economic sense to make the new Red Eagle a contemporary character, taking advantage of computer generated effects and give the hero more high tech tools to play with. It may have also seemed like a good idea to play it as a mostly serious action film. The reaction to Wisit's previous films was that Thai film audiences weren't interest in homages to Thailand's cinematic past. And yet, based on the evidence of Insee Thong, the Red Eagle films really lend themselves to the kind of parody of the secret agent out of his time as with the Austin Powers films, or something along the lines of the recent OSS 117 films.

There are only a couple of times when Red Eagle shares the unembarrassed goofiness of the original series. At one point, Red Eagle has a sword fight with the masked villain, Black Devil. The two find themselves in a giant mall, in a section of a store selling cooking ware. Black Devil's sword cuts through two small pots that Red Eagle lamely uses to defend himself. Briefly letting his guard down, Black Devil gets beaned on the head with a giant kettle. Another moment has the earnest young police detective, Chart, on a high speed chase on a motorcycle, modified with a small ice cream wagon on the side, constantly playing the tune, "Mary Had a Little Lamb". There is also a fight near a bunch of outdoor food stalls, where the Sikh detective shows off his fighting skills with deft throwing of food skewers that fly into the eyes of the bad guys. Missing are villainous ladyboys and Petchara's elaborate hairdos.

The new film takes place slightly in the future, 2016. Aside from the cultural significance of the character of Red Eagle, what would be lost on non-Thai audiences is how much of the film is a critique of the Thai political landscape. There are certainly nuances that probably passed me by. And it is the political aspects of Red Eagle that would make the film less meaningful to those unfamiliar with what has been going on in Thailand since 2006, between changes in the government, and actions of different civilian groups.

Where Wisit seemed to most successful keep his hand in the proceedings is the use of color. Much of the film takes place at night, or where everything is shaded blue, with dramatic streaks of red. The first fight scene has brief flashes of red on the entire screen. The action sequences are done as series of short, highly edited, takes. The action scenes are shot in such a way that there is no sense of loss regarding the placement and the activity of the characters. One of the visual devices used are animated x-rays showing broken bones. A sequel is promised at the end of the film, but the bigger cliffhanger might be as to if it will actually be made, and if so, will Wisit be back on the set.

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 07:15 AM | Comments (2)

January 22, 2012

Coffee Break

Cleo Moore and Raymond Greenleaf in Over-Exposed (Lewis Seiler - 1956)

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 08:04 AM

January 19, 2012

The Front Line

Go-ji-jeon

jang Hun - 2011

Well Go USA

The Front Line was Korea's entry for Best Foreign Language Film for the forthcoming Oscars. That it was the chosen film was clearly based on the assumption that this would be a film that would appeal to Academy voters. If box office was the determining factor, that film would be Sunny. Had critical consensus been a factor, Korea might been represented by The Day He Arrives which was acclaimed by one Korean group of critics. Another critics group has cited The Front Line for several awards. What has yet to be fully explored by English language writers about film is the impact Saving Private Ryan has had on the Korean film industry. In the past few years, it seems like there is at least one film about the Korean War, in part taking advantage of some of the political openness allowed in the Korean film industry. One of the best known examples is Tae Guk Gi from 2004, which has had the benefit of DVD distribution from Sony Pictures. Parts of The Front Line take from Spielberg's template, especially in its depiction of battle. But there is more to the film than a bit of visual similarities.

Much of the credit for this film should go to writer Park Sang-yeon. His novel. DMZ was the basis for the film, J.S.A. by Park Chan-wook in 2000. J.S.A was about a group of soldiers, on both sides of border diving North and South Korea, who temporarily have a truce of their own, secretly meeting on a friendly basis. That story is enclosed as part of a mystery investigated by an international, politically neutral team. Somewhat similarly, The Front Line begins with an officer who believes he is ready leave military service, sent to a battle zone to investigate the death of a captain, and the possibility of a "mole" who is facilitating communications between soldiers and their families on both sides of the war.

Not everything is as it appears or is assumed. The narrative jumps from present to past in explaining the relationship of some characters to each other, as well as their motivations. While most of the story is from the point of view of the South Korean soldiers, parts of the film show the soldiers from North Korea. Especially as Hollywood films about the Korean War cast Koreans as marginal to their own war, a film like The Front Line is instructive about how the conflict was viewed by its own people. The main part of the film takes place during the prolonged talks during the last two years of the war, where political point making by the negotiators translated into pointless military actions in the field. The story evolves from its mystery setup to that of how soldiers survive both physically and mentally. Parts of this story involve wrong headed commanding officers, an elusive North Korean sniper, death by "friendly fire", and enemy combatants who find some common ground away from battle. Most of all, The Front Line is about the waste of war.

I had written about Jang Hun's debut film, Rough Cut, a couple of years ago. Aside from the opportunity to work on a big budget film, there are some thematic similarities that could well have attracted Jang to this project. The film is initially about a man sent to uncover the truth about questionable events related to an army platoon. The film ends in a literal fog of war. Knowing that most of the main characters will die does nothing to abate the tension of the final battle in the film, a battle participants on both sides know is entirely pointless in the final twelve hours before the truce in enforced.

(Viewed as DVD screener)

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 08:18 AM

January 17, 2012

Daisy Kenyon

Otto Preminger - 1947

20th Century-Fox Region 1 DVD

The first time I was really conscious of the existence of Joan Crawford was seeing one of the films she made following the success of Whatever Happened to Baby Jane. The film I saw was The Caretakers, one of several films made dealing with issues of mental illness at the time. What I remember of that film was that Crawford was the mean, show them no mercy, bitch who ran this mental facility who was pitted against good old Robert Stack who was the humanistic, understanding medical professional. I also remember that I didn't find Crawford to be attractive, although the word "hag" hadn't yet entered my vocabulary. But in one scene, where she's wearing leotards, I was impressed by her great looking legs. I was around 12 years old at the time so my views regarding female beauty were somewhat more superficial then they are now.

It wasn't until I saw Grand Hotel for the first time at New York City's eclectic Thalia Theater, that I realized Joan Crawford had once been a babe. I would have had no problem tossing Greta Garbo for the former Lucille LeSueur. The only other time I found Crawford totally alluring was when I saw Tod Browning's The Unknown, a film I find more horrifying than any rats on a platter in Baby Jane.

And then I saw Daisy Kenyon, probably on AMC when they actually showed classic movies introduced by Bob Dorian or George Clooney's dad. I don't remember if I actually made a point of seeing Otto Preminger's film or it just happened to be on. I even introduced my mother to the film when it was on at some later date. (My mother's side of of the family was made of Bette Davis partisans.) What I do remember is that I found myself really liking Joan Crawford in that film. Dana Andrew's kisses Joan Crawford. Henry Fonda kisses Joan Crawford. Given the chance, I'd probably kiss the Joan Crawford who appears in Daisy Kenyon.

Maybe it's because I got older and my ideas about female beauty have become a bit more flexible. The DVD commentary by Foster Hirsch helps articulate some of those feelings. Crawford smiles. Crawford seems approachable. Between Preminger's direction and Leon Shamroy's cinematography, Joan Crawford actually looks lovable, rather than being the inexplicable object of man's affections because she is Joan Crawford. Until Hirsch mentioned it, it hadn't occurred to me that I was watching a 42 year old woman playing someone ten years younger. The age of the character never seemed important to me. Hirsch mentions a "softness" about Crawford that is absent in most of her other performances. Even in the other MGM films I've seen that were made after Grand Hotel, Crawford lacks the warmth that Preminger was able to convey. Maybe it's all acting. Maybe it's a few tricks with make-up. What I do know is that Stephen Harvey, an acquaintance from my New York days, who wrote a little book on Crawford, might well be laughing from his particular perch in movie heaven. And I also know that I love Joan Crawford in Daisy Kenyon.

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 08:37 AM

January 15, 2012

Coffee Break

Shu Qi and Emilie Ohana in New York, I Love You (Randy Balsmeyer - 2009)

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 08:22 AM | Comments (2)

January 12, 2012

Sweet Love, Bitter

Herbert Danksa - 1966

Efor Films All Region DVD

One of my best memories of studying film at New York University was encountering Lewis Jacobs. Best known for his book, The Rise of the American Film, we had some lively discussions both in and out of class. I knew he had also co-written a screenplay to a film I had read about, but had not seen, and had wished that he had shown it in class. Sweet Love, Bitter might not be lost classic, but it is very much worth seeing both for a glimpse of a past era, and as an example of a true independent film.

I haven't read the source novel, Night Song, by John A. Williams, but I have read one of Williams' other novels, which told about being a struggling black American novelist in New York City, in the Fifties. I wouldn't be able to judge the veracity of the novel or film's portrayal of a fictionalized version of Charlie Parker. And I also don't think that much familiarity is needed, because the real focus is on the interconnected relationships between the main characters: "Eagle" Stokes, a famed jazz sax player to often controlled by his drug addiction, David, a university professor who tries to drink away the guilt for causing the accidental death of his wife, Keel, the owner of a coffee shop who acts as a caretaker for "Eagle" and takes in David to help run the coffee house, and Della, Keel's girlfriend. Della is the least defined character in the film, and the interracial relationship between her and Keel, while somewhat radical in an American film at the time, doesn't carry the same weight as the sometimes volatile friendship between the three men.

The inspirations of cinema verite, French New Wave, Cassavetes, and Ingmar Bergman, are easy to spot, but what's best is seeing a film shot on the streets of New York and Philadelphia back in 1966. No sets here, but real apartments and night clubs. Not only are the apartments small and cramped, but sometimes truly grimy, very much lived in. And this is what makes Sweet Love, Bitter worth seeing. Even if one deems aspects of the story to be contrived, the characters exist in a very real, very unpretty world. The camera pans on the patrons in the bars and nightclubs, and these look like people from the streets, not from some casting agency. I'm not absolutely sure, but Professor Jacobs may have made a cameo appearance sitting in at Keel's coffee house.

The production is unique confluence of talent. Herbert Danska did some documentary work before leaving filmmaking for artistic expression as a children's books illustrator. This is the only film credit for Lewis Jacobs. Don Murray was in a transitory period between his early Hollwood stardom of the late Fifties and early Sixties, and a career primarily in television movies and series. This would be Dick Gregory's only substantial acting role. How much of the performance was improvised, I couldn't say, but there is a sense of rawness that adds laughter and anger. Murray reputedly was responsible for the casting of Diane Varsi, a Hollywood dropout who acted with Murray in From Hell to Texas, the same production noted for the contentious relationship between director Henry Hathaway and Dennis Hopper. In smaller roles, Bruce Glover, more famous for his son, Crispin, and John Randolph, one of his first big screen credits following being blacklisted. Sweet Love, Bitter did prove to be an effective launching pad for Robert Hooks, his first feature film, to be followed by work with Otto Preminger, and television series stardom in N.Y.P.D..

Whether the film is in any way "about" Charlie Parker is besides the point. After forty-five years, what does stand are the thoughts on art and artists, as well as the often taken for granted exploitation of artists. Even the racial aspects to the film, so topical at the time, are still issues that have not been fully resolved. Most pointed is a moment of truth between David and Eagle, where David fails in the courage of his stated convictions. Even more timeless is a brief moment when a would-be admirer of Eagle, a young white woman, eagerly tells the musician that she would do anything for him. The glimmer of hope for some kind of rendezvous sags to disappointment when constantly broke Eagle asks her to lend him twenty dollars.

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 08:28 AM

January 10, 2012

Gurozuka

Yoichi Nishiyama - 2005

Synapse Films Region 1 DVD

Is this a horror film primarily aimed for a young female audience? It looks that way for a couple of reasons. First, the cast is all young women. Second, even though there is a bit of chatter about two of the characters being "in a relationship", and there is a scene of one of the women taking a shower, there is nothing going on that would be considered titillating. I would imagine that this film would have been rated something like the equivalent to PG-13 in Japan, with only some of the bloodiness being tilting towards something a bit more extreme for stateside audiences.

The story is about a group of six students and a teacher, part of a movie club, who go to a secluded house in a remote, wooded area. One of the students has discovered an old film made seven years ago, by some previous students, about a vengeful ghost wearing a Noh mask. Part of the film features an on screen murder. There are rumors that what was recorded on film was real. The attempt to discover the truth, as well as recreate the older film, causes havoc and death.

Food disappears. Cell phones and money disappear. Eventually some of the students disappear. When those that are still around get a drift of what's happening, and assume that they are being haunted by the mysterious masked woman they saw in the film, it is understood that the deaths are staged in ways that refer to five categories of Noh plays. While this isn't discussed deeply by any means, it provides a nice contrast to similar western horror films that are either self-referential or refer usually to any horror film usually no older than Night of the Living Dead. There are some of the usual horror film tropes, the point of view camera shots, the "gotcha" moments, and the discovery of being in the one place where there is no cell phone signal. The use of the noh mask in Japanese horror films, while effective, has not been overused.

There is nothing of substance about the creative team behind Gurozuka, although a good part of the credit would seem to go to Tadayoshi Kubo, who created the story and was one of the film's producers. Kubo's high watermark would be as a producer of Seijun Suzuki's Pistol Opera. IMDb is not the most reliable source for Asian films, but it seems like Gurozuka marks the end of a four film filmography by Yoichi Nishiyama, as well as composer Ryuji Murayama, whose creative use of scratchy guitars and bells makes the score worth mentioning. Yukari Fukui has made a career for herself as a voice artist, but makes for an engaging screen presence with her cute overbite. Yuko Kurosawa provides most of the eye candy during her time onscreen.

The film is a curious choice for the return of Synapse Films' Asian Cult Film Collection. Unlike previous releases, Gurozaku is not particularly gory, nor is there anything erotic. Nor is the film just flat out idiosyncratic like the films of Minoru Kawasaki. I would hope that the brain trust of Synapse looks beyond Japan for some movies in need of DVD rescue, perhaps the acclaimed Thai thriller, Slice, from the director of a couple of the Art of the Devil films, Kongkiat Khomsiri, and written by Wisit Sasanatieng, most famed for his Tears of the Black Tiger. Or maybe something from Indonesian filmmaker Joko Anwar. For what it is, Gurozaka is better than what I had expected, but without either audacity or originality to make the film of more than minor interest.

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 08:01 AM

January 08, 2012

Coffee Break

Vittorio Gassman and Gloria Grahame in The Glass Wall (Maxwell Shane - 1953)

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 08:37 AM

January 05, 2012

Air Hostess

Kong zhong xiao jie

Yi Wen - 1959

Panorama Entertainment Region 3 DVD

"Tis the season to be pummeled by various studios with screeners, bearing the words, "For your consideration". And yes, some of these films have already been considered as award worthy by critics groups. For myself, I'm already tired of the sense of self-importance, and worse, the joylessness of these films. Sometimes you need to see a film that really isn't aspiring to be anything more than entertainment.

Enter Grace Chang. It was a couple of Decembers ago when I went through her five DVD box set. Any of her other films are now separate purchases. And there is nothing in Air Hostess that is expressly artistic, but it sure is fun. There's also nothing very original, but this is a film made at a time when the Hong Kong film industry would shamelessly crib from Hollywood without fear of consequences. It doesn't take much to imagine Doris Day, Lauren Bacall and Rock Hudson in the roles respectively taken by Chang, the lean and lovely Julie Yeh Feng, and the solid Roy Chiao.

Chang plays Keping, a young woman who is constantly reminded by her mother, and a drip of a would-be suitor that she's of marriageable age. Maybe her motivations for being what is called in this film, an air hostess, is questionable, mostly as a way of avoiding marriage to a guy she wants to keep at arms length, in a profession that at the time required that the young women remain single. Even if being an air hostess keeps Keping from doing what she really wants, which is basically to sing and dance, it also allows her to bide her time to figure out what she wants out of life. And while Air Hostess can't really be described as being feminist, at least in the western sense, it does present a narrative involving women having professional aspirations and a loosening of the traditional filial ties.

Keping proves to be a natural at her job, proving her ability to offer coffee in English, French, and three different Chinese dialects, making friends with the other hostesses, and carrying on an on and off relationship with Daying (Chiao). Along the way, smugglers of fake jewelry are caught, Keping finds opportunities to sing and dance, and a marriage is conducted in mid-flight.

The film seems to be geared to a younger, more cosmopolitan Hong Kong audience. Keping travels to Singapore, Taipei and Bangkok, and the film would serve as reminder of the wonders of air travel, with an emphasis on pan-Asian connections. A song about Taiwan is a reminder of that time when Hong Kong and Taiwan were more closely linked as part of the Chinese diaspora following the communist takeover of mainland China. Chang and Chiao spend time wandering around various temple grounds near Bangkok, the kind of scenic meandering that could well have inspired parts of Wong Kar-wai's In the Mood for Love.

Based on what I've read previously, How to Marry a Millionaire must have been very popular in Hong Kong, providing a template for several films. Jean Negulesco's film had a running gag with Marilyn Monroe bumping into everything without her glasses. In Air Hostess, one of the women is perpetually clumsy, allowing her to "meet cute" with a flight navigator when she slips on the airplane stairway. One of the musical themes is a barely disguised reworking of the song, "I Cain't Say No" from Oklahoma, so obvious that Richard Rodgers should have received credit. Younger viewers may find themselves aghast at the sight of propeller airplanes and passenger meals handled with bare hands. For myself, at a time when the Hollywood machine wants to browbeat me into taking some of their very current films seriously, a detour into the past of cheerful silliness can be its own reward.

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 08:21 AM | Comments (1)

January 03, 2012

Nichiren and the Great Mongol Invasion

Nichiren to moko daishurai / Nichiren - A Man of Many Miracles

Kunio Watanabe - 1958

I first read about this film, mentioned by Donald Richie, without knowing anything about it. The title meant nothing to me until a few years later. Being a Nichiren Buddhist not long after this introduction to Japanese film, my interest was piqued. I even bought the Japanese DVD, even though it lacks English subtitles. Having been a Buddhist for about thirty-eight years, I pretty much know the main narratives about Nichiren. I had no idea that there was a subtitled edition of this film until I browsed through a list of DVDs starring Raizo Ichikawa from, shall we say, an independent dealer of subtitled Japanese films.

The period of life covered here starts from the day Nichiren, a Buddhist monk, declares that the way to practice Buddhism correctly is to chant, "Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo", essentially the title of the Lotus Sutra. The film ends when the huge Mongol invasion is repelled by one very strong typhoon that sinks hundreds of ships carrying thousands of soldiers, off the coast of Japan. The basics of the story are true, even if some of history is changed. I don't know if anyone experienced any kind of epiphany when watching the film, or any kind of change of faith. To me the main motivation of the filmmakers was more of an emphasis on historical spectacle, a chance to show what the special effects department could do, and to keep some of Daiei Studios big stars busy.

Paul Schrader wrote about what he called "Over-abundant" means in his book, Transcendental Style in Film, using Cecil B. DeMille's work, primarily in his second version of The Ten Commandments as his main example. For subtlety, look elsewhere. Here the soundtrack includes a chorus melodiously chanting "Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo" to music. A scene with Nichiren about to be beheaded features the would-be executioner electrocuted by some very unconvincing lightning. About to be dumped at Sado Island, riding a small boat buffeted by some big waves, Nichiren takes a stick, points it at the water, and the kanji for "Nam-Myo-Ho-Renge" appears superimposed on the now calm sea. Some of the dialogue is recognizably from the letters of Nichiren, but when people speak to each other, it is not in conversation but more of an exchange of overly dramatic declarations.

As often happens with historical films, the makers are a bit loose with the facts. Even with allowances for dramatic license, I have to wonder if there was anyone to give some advice on the set regarding Buddhism. At one point, Nichiren is seen having a small enshrined statue in his house, when one of the main parts of this Buddhist practice is the absence of anything other than chanting to a scroll, known as the gohonzon. I also have to assume that when a gohonzon is actually shown, it is a movie prop, and not the work of a temple based calligrapher. Nichiren's parents appeared much more prosperous than is suggested by the biographical writings, especially considering that this is a caste bound society where fishermen were considered lower class. With the exception of the shack in Sado Island, Nichiren's various residences are much bigger and nicer than one would expect from someone who relied on the donations of his believers.

Kazuo Hasegawa, with his baby face and luxurious eyelashes, may have been a big star. At age 50, he was also a bit too old to play someone in his thirties. Given that extant artwork isn't the most accurate indicator of what anyone in 13th Century Japan, Hasegawa's Nichiren is no more or less true than Jeffrey Hunter, Max Von Sydow, or anyone else who took on the role of Jesus. Back when he was still groomed to be a matinee idol, Shintaro Katsu plays Shijo Kingo, a famous samurai believer, while Raizo Ichikawa appears as a government official and seemingly the only straight-shooter in the otherwise corrupt shogunate. Kurosawa stock player Takashi Shimura has a small role as a peasant who helps feed and protect Nichiren. Simply viewed for the appearance of a cast from Japanese cinema's golden age makes Nichiren and the Great Mongol Invasion entertaining. It might have been somewhat better had Kunio Watanabe's ideas for filming in wide screen extended to more than several lateral tracking shots, or having the actor run straight stage right or stage left across the screen. A smarter film that used a more sophisticated means of conveying Nichiren Buddhism was written about here. Still, I'm comfortable enough with my own faith and how it is depicted in film to giggle when, in response to Nichiren's stating to a young samurai that he predicted the Mongol invasion, the subtitle reads, "No kidding?".

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 08:54 AM

January 01, 2012

Coffee Break

Tilda Swinton and Isaach De Bankole in The Limits of Control (Jim Jarmusch - 2009)

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at 08:42 AM | Comments (1)