« Kiss the Blood Off My Hands | Main | Backlash »

August 04, 2020

The Tony Curtis Collection

The Perfect Fulough

Blake Edwards - 1958

The Great Imposter

Robert Mulligan - 1960

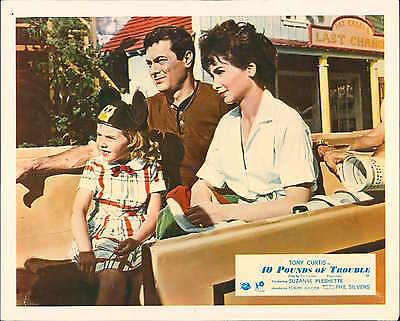

40 Pounds of Trouble

Norman Jewison - 1962

KL Studio Classics BD Three-disc set

Usually, when I've covered blu-ray release sets, it's centered on a genre or filmmaker. What made me interested in this three disc set of films starring Tony Curtis is that the three films in question were all early works by directors who would become major hitmakers within a few years, all with films that became iconic. In terms of the star's career, all three films were made during the time Curtis was under contract to Universal for a second seven year period, but with the option to make films with other studios. It's generally the films Curtis made outside of Universal that have sustained the most interest over the past decades. But there is the simultaneous interest of seeing both how Curtis, especially after his Oscar nominated performance in The Defiant Ones, exercised power in working with directors who were also given the chance to establish their own respective styles that would be more apparent in future work.

The Perfect Furlough was one of four movies starring Curtis in 1958, a year that included Delmer Daves' Kings Go Forth, his only Oscar nominated performance in The Defiant Ones and a second film with then-wife Janet Leigh, The Vikings. Ms. Leigh also appeared in one movie without Curtis that year, a potboiler Universal hacked up and tossed in a ditch, Touch of Evil. Younger readers may not be aware that Tony Curtis and Janet Leigh were the power movie star couple of the 1950s, making five films together as well as being major stars individually. The premise of Stanley Shapiro's script is that Curtis plays a womanizing soldier, one of 104 assigned to a remote base in the Arctic. After seven months of a year long assignment, the soldiers are finding their isolation difficult. Leigh plays the Army psychologist who comes up with the idea that the soldiers will find vicarious release through one soldier who is allowed a three week furlough. Egged by Curtis, the soldiers all describe their perfect furlough as spending three weeks in Paris with an Argentine bombshell actress, played here by an actual Argentine bombshell, Linda Crystal. Curtis finagles his way to winning a lottery, with the rest of the film taking place in a studio lot Paris. Much suspension of disbelief is needed not only for the plot, but the plot twists that take place.

What is of interest are the sight gags that would be re-worked later, primarily in the Pink Panther series. King Donovan appears as the hapless officer who breaks a pointer and walks into closed doors. One still funny bit involves a strategically placed bottle of champagne. Both Leigh and Crystal tumble into giant vats of wine. Edwards' visual style involves very little cross cutting between characters, keeping even his stars in two-shots and group shots within the CinemaScope frame. The film was the second of four films Curtis and Edwards made, followed the next year with Edwards' first major hit, Operation Petticoat, also at Universal.

The commentary track is most conversational between historians David Del Valle and C. Courtney Joyner that goes off in several tangents, although honestly, how could it not? The discussion covers the production of the film and its place in the careers of the primary talent, as well as placing it in the context of the era of production. While the commentary succeeds in being entertaining and mostly informative, I was astonished that of the several supporting players mentioned, nothing was said about Marcel Dalio, appearing here as the winemaker passing his wisdom of love to Curtis. To their credit, Del Valle and Joyner are honest about the film's weaknesses and those aspects that reflect the sexual attitudes of the time, as well as being observant about how the film works in anticipating some of the future films by Blake Edwards.

The Great Imposter was the second of two films Curtis made with Robert Mulligan, following The Rat Race, also from 1960. It was Mulligan's third feature and like The Rat Race essentially a commissioned work, though Mulligan had a major hand in casting of the supporting roles. This is a highly fictionalized story of a high school dropout, Fernando Demara, Jr., who through a reading of people and a photographic memory managed to take on a variety of identities and occupations, most infamously as a Canadian naval surgeon who completed nineteen successful surgeries on board a ship in battle off the South Korean coast. Demara was a celebrity at the time the film was made, profiled in Life magazine, and the subject of a best selling biography published in 1959. The film is lighter in tone than the biography, tailored more to Curtis' onscreen persona. The real Demara was also physically heavyset, unlike Curtis' lithe go-getter. Universal at this time was the most conservative of the big studios, but with Curtis demanding roles with greater dramatic range, there was some drama mixed in with the whimsy.

Although the film was well received at the time, I don't think it has aged as well. The Rat Race, dominated as it is by Garson Kanin's screenplay based on his ten year old play benefits from some on location shooting with Curtis and co-star Debbie Reynolds on the streets of New York City. Even though Mulligan was respected enough by his peers to get nominated for a Directors Guild Award, The Great Imposter lacks the vitality and sense of place of the earlier film. Where it works best as a warm-up for Mulligan's best films is an early scene of Demara's depression era childhood. In two years, Mulligan would make To Kill a Mockingbird. There are also The Other and Man in the Moon, among the better films. Kat Ellinger's commentary reviews how Mulligan was part of the generation of film directors who were trained in television dramas, often shown live at that time, who made their feature debuts in the late 1950s and early 60s. The Great Imposter was also noted for having several major names in supporting roles, notably Karl Malden as a friendly priest who provides some dramatic continuity. Others may delight in seeing the relatively unknown Frank Gorshin as a scheming convict whose constant villainous laugh anticipates his role as The Joker in the Batman TV series.

By the time one gets to 40 Pounds of Trouble, there is a noticeable inverse relationship between the quality of the films and the trajectory of the respective director's careers. Norman Jewison was hand-picked by Curtis following a television career of specials devoted primarily to musical performers, most notably Judy Garland. In the New York Times, Bosley Crowther's summed up his opinion, "The trouble with 40 Pounds of Trouble is that it is just too hackneyed and dull." Time has not helped Jewison's feature debut, which hardly suggests that the director would be the recipient of three Oscar nominations for Best Director including Best Picture winner, In the Heat of the Night.

The film is an uncredited remake, the second, of the Shirley Temple film, Little Miss Marker, about a five year old girl left behind by her gambler father, who has temporarily left in order to pay off a debt. The source is a story by writer Damon Runyon, famed for his tales of gamblers, gangsters and show business types and assorted riff-raff in 1930s New York City. Runyon should be happy that his name is not on the credits for this film, an updated version that takes place mostly in Lake Tahoe, Nevada, with a frenetic chase taking place in Disneyland. There was a fourth version made, also with Curtis, this time supporting his former acting school colleague Walter Matthau.

While Crowthers rightly complained about the weak screenplay, he was oblivious to Jewison's hand in the visuals. In retrospect, it would seem like Jewison was hoping to use as many ideas about making the film as cinematic as possible, starting with an elaborate long take of Curtis walking through the poker tables and one-armed bandits of the casino he manages, weaving in and out of people and multiple conversations. It's an overhead traveling crane shot that may not rival the opening of Touch of Evil, but it is quite striking, as well as evident of the kind of trust Curtis placed in his novice director. The montage of gamblers, including a few direct overhead shots looks straight ahead to The Cincinnati Kid, while the use of split screen in a three way conversation is future practice for The Thomas Crown Affair. Much of the film is devoted to pop culture references very current in 1962, though gags involving John and Robert Kennedy are now painful rather than funny.

The conversational commentary track, again with Ellinger teamed with podcaster Mike McPadden, points out how 40 Pounds of Trouble is of interest as a document of its time. Jewison shot on location in a Disneyland that substantially no longer exists, with many of the rides aged out. Add to that other filmmakers at that time may well have settled for second unit shots, with the actors filmed in front of a blue screen. Ellinger and McPadden also note Jewison's place in the changes in the way Hollywood films were produced. 40 Pounds was enough of a hit that Jewison became a house director at Universal for his next three films, two which were major hits starring Doris Day. As soon as he was tapped to direct The Cincinnati Kid, Jewison was able to make the transition while the old studio system was collapsing, with greater choice in projects, shooting on location, with a freer hand in onscreen and production talent.

Circling back to the star, Ellinger and McPadden discuss Curtis's career and his frustration at not being taken seriously as an actor. It should be noted that 40 Pounds followed The Outsider, a downbeat biographical drama. The story of Ira Hayes, the Native American soldier who helped raise the flag at Iwo Jima, the film was Universal's one attempt with Curtis in a straight drama, and a box office failure. Curtis probably felt he had to go back to formula to maintain his stardom. By the time his contract with Universal had ended, Curtis had one major hit, again with Blake Edwards and The Great Race, followed by diminishing returns through the rest of the 1960s. Even starring in The Boston Strangler was enough to break the typecasting.

The greatest appeal of this three disc set will be for the Tony Curtis fan who will enjoy his presence for its own sake. For serious cinephile, the interest will be in the early development of the three directors, as well as an incidental tracing of the shifts in Hollywood filmmaking and the visible ending of the studio system at the most conservative of Hollywood studios.

Posted by Peter Nellhaus at August 4, 2020 07:29 AM